America Has a Right to Housing … for the Rich

December 10, 2018 is the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1948, in the aftermath of the fall of the Nazi regime, the United States joined many countries in the world and signed the Declaration. Several of the rights listed in the document were already within the U.S. Constitution, but some were not. We have done particularly poorly in living up to the Declaration’s call for a right to an adequate standard of living, including food, housing, and medical care.

There is still hunger in America, but we do provide food assistance to help feed the hungry, and we are at least debating providing medical care for all. However, despite a massive and growing affordable housing crisis, there is little discussion of the need to uphold a right to housing. In fact, our housing policy seems like its end goal is large scale homelessness rather than the provision of affordable housing.

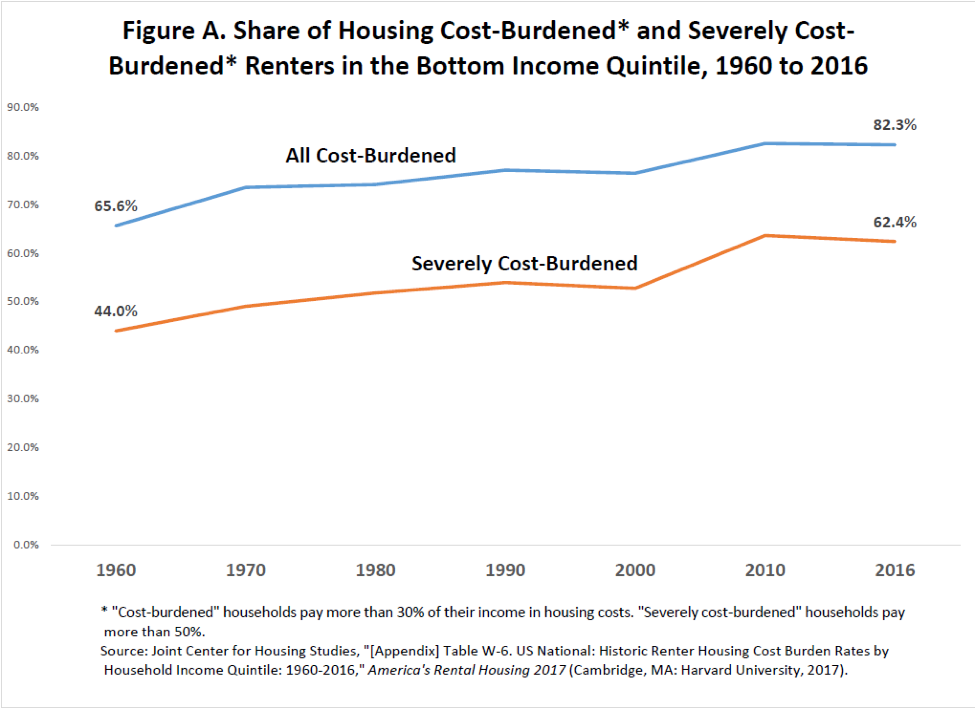

Figure A shows that for low-income Americans, renting has become increasingly unaffordable. In 1960, two-thirds of renter households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution were cost-burdened, meaning that they paid more than the recommended ceiling of 30 percent of their household income on housing. At that time, 44 percent of those households were severely cost-burdened—they paid more than 50 percent of their income on housing. It should be clear that when households are paying that much in rent, they are struggling to maintain a decent standard of living. Further, it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, for those households to save for emergencies, much less to build wealth to attain long-term economic security and achieve upward economic mobility.

Since 1960, it has only become more difficult for low-income renters. There has been an overall upward trend in the rate of cost-burdened renters, with no significant decline. Today, four-fifths (82.3 percent) of low-income renters are cost-burdened and three-fifths (62.4 percent) of them are severely cost-burdened.

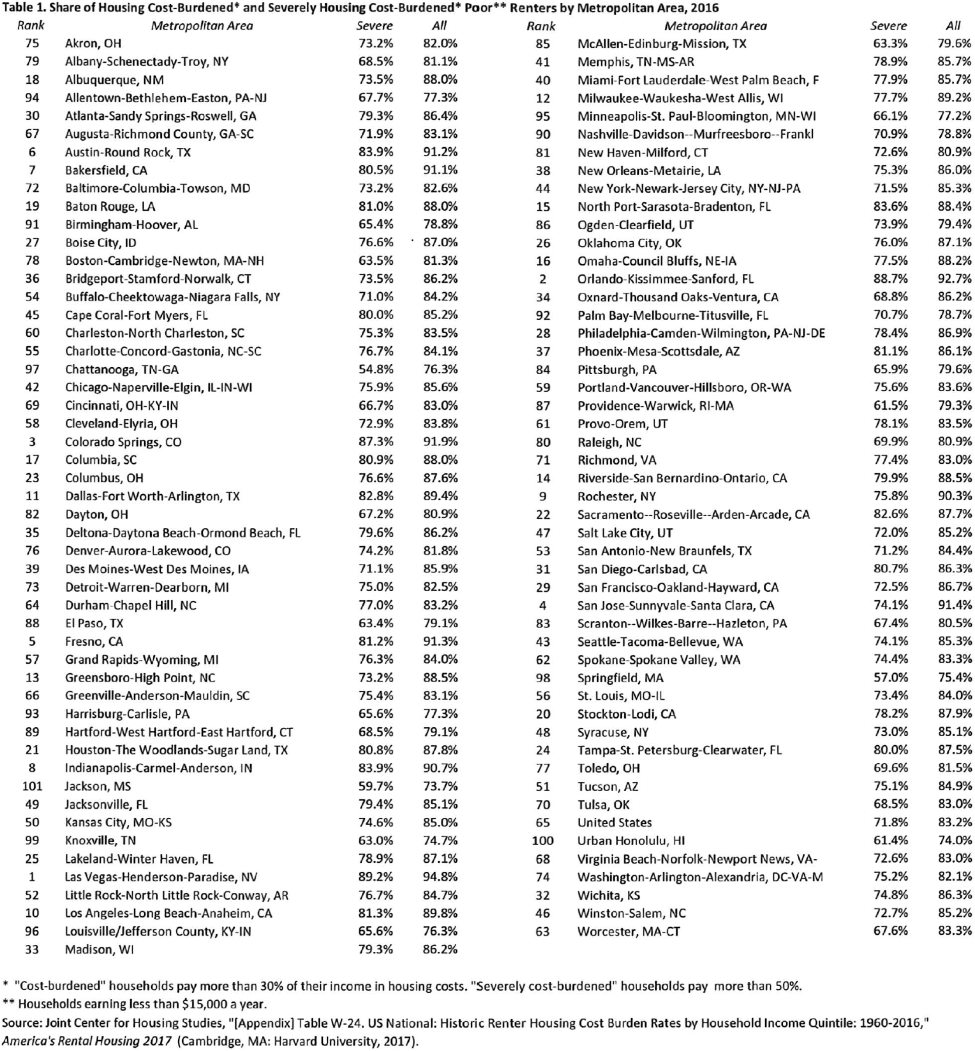

It would be wrong to think that the problem of unaffordable housing is limited to one region or just a few metropolitan areas. The analysis of cost burdens in major metropolitan areas (see Table 1 below) by the Joint Center for Housing Studies shows that this is a national problem requiring a federal response. In 101 of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas, a majority of poor renters are not merely cost-burdened, they are severely cost-burdened. For example, in Jackson, Mississippi, ranked 101 in terms of cost burden—the best of the lot—nearly three-quarters (73.7 percent) of poor renters are cost-burdened and more than half (59.7 percent) are severely burdened. In Tucson, Arizona, rank 51, 84.9 percent are burdened and 75.1 percent are severely burdened. In Columbus, Ohio, rank 23, nearly 90 percent are burdened and nearly 80 percent are severely burdened. The metro area with the highest rate of cost-burdened poor renters is not San Francisco or New York, but Las Vegas. In Las Vegas, Nevada, nearly all poor renters—94.8 percent—are cost-burdened, and 89.2 percent of them are severely cost-burdened.

Our response to this national problem has gone from bad to worse. It is bad, in part, because we spend the vast majority of our federal housing dollars on the rich. Robert E. Friedman, in his book, A Few Thousand Dollars: Sparking Prosperity for Everyone, notes that the “wealthiest 5 percent of taxpayers get more than $200 billion in annual homeownership tax breaks—more than the bottom 80 percent combined.” He also notes that these “upper-income tax subsidies are four times the entire annual budget of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development”—the agency that is supposed to help provide housing for the poor. Clearly, policymakers have constructed our housing policy to give money to rich people.

The situation has gotten worse because we have moved to relying on the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) to provide affordable housing. Although “low-income” is in the name of the tax credit, the credit is used by and helps wealthy investors, banks, and real estate developers profit from the construction and preservation of affordable housing. This is yet another way our housing policy gives money to the rich.

The LIHTC is inadequate for meeting the housing needs of the poor, and not simply because there are too few credits available. Because the LIHTC is a tax credit, the amount of housing created depends on how much rich people use the tax credit—not on the amount of housing that is needed. The Great Recession led to a decline in the amount of credits used, and the Republican tax cuts pasted last year are also expected to reduce the amount used. Additionally, the LIHTC is not designed to meet the needs of the poorest renters. Finally, the housing created by the LIHTC is only required to be kept affordable for a limited period of time. In summary, the LIHTC does not provide the country the amount of affordable housing needed, at all the price points that are required, and any housing needs that are addressed adequately by the LIHTC are met only temporarily. That the United States relies on such a weak mechanism to build affordable housing shows that we are not committed to a right to housing.

If, in this 70th anniversary year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we wish to move toward a right to housing, we need to stop using our housing dollars to benefit the rich and devote those dollars to helping the poor. We need to repair and invest in public housing and dedicate more funding to housing vouchers. We also need to remove unnecessary zoning regulations. Our country spends enough on housing to make it affordable for all. We simply have to stop spending our housing dollars on the rich and put those dollars where they are truly needed.