34 Years Later, Did We Learn Anything from Love Canal?

In a post written shortly after the Love Canal disaster, Eckardt Beck, the EPA Director at the time, very presciently said:

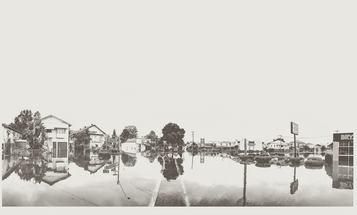

A protest by Love Canal residents, ca. 1978.

A protest by Love Canal residents, ca. 1978.

“[Q]uite simply, Love Canal is one of the most appalling environmental tragedies in American history. But that's not the most disturbing fact. What is worse is that it cannot be regarded as an isolated event. It could happen again--anywhere in this country--unless we move expeditiously to prevent it.”

Decades after the Hooker Chemical Company stopped using the canal as a toxic waste dumping site, 82 different compounds began to leach their way into the soil due to rotting drum containers. Hundreds of homes--and a public school-- had been built on the site and after a massive rainstorm caused an explosion, toxic chemicals were leaching into their backyards and basements. Even though residents had been complaining of strange smells and odors for year, it wasn’t until 1978 when officials started to take action and shut the school and relocated families—many of whom had already suffered significant health impacts from living by the canal.

In his post, Beck stated, “We suspect that there are hundreds of such chemical dumpsites across this Nation…The presence of various types of toxic substances in our environment has become increasingly widespread -- a fact that President Carter has called ‘one of the grimmest discoveries of the modern era.’” At the time, over 30 years ago, chemical sales were $112 billion per year. That number has at least tripled and the top 50 chemical companies alone sold over $330 billion of chemicals in 2011. Sadly, even though there are more chemicals around now, the protections that were put in place after the Love Canal tragedy are slowly being eroded.

In the wake of Love Canal, the EPA’s Superfund program was established to clean up toxic waste sites. For a while, a tax was placed on polluting industries, like the oil and chemical industries, with the money going into a cleanup trust fund. It made perfect sense: polluting industries should pay to cleanup their messes and not leave the burden on taxpayers. Yet when those taxes expired in 1995, Congress refused to renew them and now the fund has no money—meaning there are no dedicated funds to cleanup these toxic sites. Instead, taxpayers must now pay for the cleanup and with EPA’s budget continuously being cut, fewer and fewer funds are available to identify and cleanup toxic sites.

At the same time, record amounts of money are being spent lobbying against hazardous waste regulations, most recently seen in the battle over coal-ash regulations. The EPA is continually under attack by right-wingers wanting to take authority away from the agency. Cost-benefit analysis is being used to force agencies to justify regulations, even though it is a deeply flawed method of analysis. The reality is that the public is again taking on the risk and costs of cleanup while corporations are padding their profits and skirting their responsibilities.

Beck ended his post with a call to action stating, “[I]t is within our power to exercise intelligent and effective controls designed to significantly cut such environmental risks. A tragedy, unfortunately, has now called upon us to decide on the overall level of commitment we desire for defusing future Love Canals. And it is not forgotten that no one has paid more dearly already than the residents of Love Canal.” Unfortunately, 34 years later, it seems the desire to protect profits and reduce costs to corporations trumps the desire to defuse future Love Canals.