Introduction

For our democracy to thrive, the freedom to vote must be fiercely protected for all citizens, regardless of class or privilege. The right to vote provides the foundation that makes all other rights possible.Yet, much work needs to be done to be sure our election system works for all Americans. This is particularly true when it comes to ensuring that the voter registration process is widely accessible and easy to navigate. Historically, and still to this date, lower-income Americans are much less likely to be registered to vote compared to their more affluent counterparts, which in turn leads to voter turnout rates that skew our electorate and undermine representative democracy.

In order to vote, eligible citizens must first register—a step in the political process that has historically been difficult to navigate and subject to onerous burdens designed to exclude citizens of color and lower-income citizens from easily casting a ballot.

In fact, the United States is one of only a few democracies that places the responsibility of registering primarily on each individual voter, rather than making government accountable for ensuring that eligible persons are registered. Not surprisingly, obstacles to registration result in fewer people who are registered to vote. Disparities in voter registration rates directly result in disparities in who votes in any given election, leaving many voices unheard.

The first major overhaul of election registration laws and practices—the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA)—eliminated some of the most obvious obstructions to voter registration, such as literacy tests and poll taxes. It also provided federal oversight over election procedures in states that had deliberately impeded voter registration historically and had low voter turnout. The impact of the VRA was clear and immediate: In the five years after its enactment, as many African-Americans were registered to vote in the South as had been registered in the previous 100 years. In Mississippi, for example, African-American registration increased from below 6.7 percent in 1965 to 60 percent in 1968.

The VRA greatly improved the process of registering and voting for millions of Americans, yet decades after its passage, our nation continued to suffer from wide gaps in voter registration by both race and class. Local laws and procedures often created a complicated maze for citizens to navigate just to register to vote. For example, long after the VRA was enacted, many states still required eligible persons to appear in person at a registrar’s office. And, often there would be only one registration office in an entire county with limited hours and/or there would be no registration office in communities of color. As a result, millions of eligible persons remained unregistered

Recognizing that the voter registration process remained a major obstacle to voting, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) in 1993 in a deliberate attempt to increase voter participation. Fundamentally, the NVRA was designed to streamline and facilitate the process of voter registration and provide uniform registration procedures for federal elections in order to end many of the confusing, and often obstructive, laws affecting voter registration across states and localities. In particular, the NVRA set the first ever national standards for mail-in voter registration, required states to provide registration at public agencies, outlawed the purging of voters solely for non-voting, and established the nation’s first federal standards for voter list maintenance and the first national voter registration application, required states to provide registration at public agencies, outlawed the purging of voters solely for non-voting, and established the nation’s first federal standards for voter list maintenance and the first national voter registration application.

Since its adoption twenty years ago, the NVRA has successfully registered millions of eligible voters and led to important increases in voter registration among lower-income Americans. This brief highlights the key provisions in the act that were designed to expand voter registration opportunities, describes its impact on voter registration rates, and provides recommendations to ensure the act continues to expand voter registration opportunities for millions of Americans.

Key Voter Registration Components of the NVRA

The NVRA facilitated voter registration in three key ways by requiring:

- state motor vehicle offices to offer voter registration;

- public assistance and disability offices to offer voter registration; and

- states to accept mail-in registration forms.

Under Section 5 of the NVRA, eligible citizens can register to vote when they apply for a driver’s license. Any change of address submitted to the state motor vehicle office is also forwarded to election authorities, automatically updating the eligible voter’s registration.

Section 6 of the NVRA helped ease voter registration by requiring that states accept a standardized federal mail-in application as a means of registering to vote. Instead of having to submit an application in person at a registrar’s office, eligible voters can use the federal mail-in form or a state mail-in form that meets the same requirements as the federal form. This provision is particularly helpful to eligible voters that cannot make a visit to a registrar’s office during normal business hours, and it greatly facilitates voter registration drives.

Section 7 expands voter registration access by requiring any office that provides public assistance, as well as state-funded programs primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities, to also provide voter registration services. Beyond just providing registration forms, Section 7 requires that applicants receive the same level of assistance when completing voter registration forms as is provided with completing the agencies’ own forms, and requires agencies to transmit completed registration applications to the appropriate election official.

Together, these three provisions in the NVRA have assisted millions of eligible Americans to register to vote and have started to narrow the voter registration gap, with improvements in the percentage of lower-income citizens who are registered to vote.

The Voter Registration Landscape before NVRA’s Passage

Today, many of us take for granted the availability of voter registration applications, whether through the motor vehicle department, a public assistance or disability office, a voter registration drive, or a mail-in application that can be printed out from a website. But, the reality is that prior to the NVRA’s passage, registering to vote and even obtaining a voter registration application was often quite confusing and complicated. There were no uniform standards among the states and, for many eligible voters, registering to vote required a trip to the election registrar’s office, often open only during business hours. In sixteen states, voters had to report to a central office to register, as late as the mid-1980s.

Some states had even more extreme barriers to voter registration. Mississippi, for example, had a dual registration system that required eligible voters to register separately for state and municipal elections up until 1987. Mississippi also left it to the discretion of each individual county clerk whether to allow registration books to be removed from the county clerk’s office to conduct voter registration. As a result, many counties had no satellite sites where eligible voters could register. This restriction left many eligible voters no option except to go to the county clerk’s office, regardless of how far it was and how restrictive the office hours were.

Very often, voter registration also required filling out a complicated form and proof of identity and residence. Residency requirements varied widely from one day to two months and as quoted in Richard Wolfinger and Steven J. Rosenstone’s book, Who Votes?

...it is hard to forget that it is Election Day… The process of prior registration, on the other hand, is much more diffuse and vaguely defined. Most people know that there is some kind of deadline, perhaps, but few people would know just when it was or where it was necessary to go.

Third party voter registration efforts also often faced barriers, such as in Indianapolis where volunteers were only given 25 voter registration forms at a time. Each time volunteers needed more forms, they were required to secure permission from representatives of one of the political parties and the county registrar and undergo training, no matter how many times they had been trained before. In other areas, such as Virginia and Massachusetts, volunteers were told that certain locations, such as public housing or public welfare offices, were off limits for voter registration outreach. During the 1980s, a few states offered voter registration at their motor vehicle offices, but the majority did not.

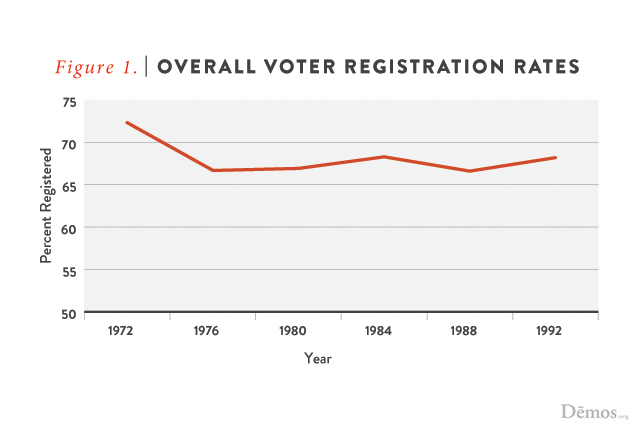

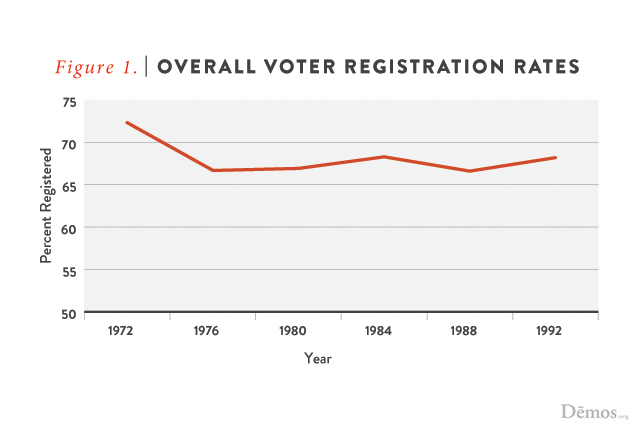

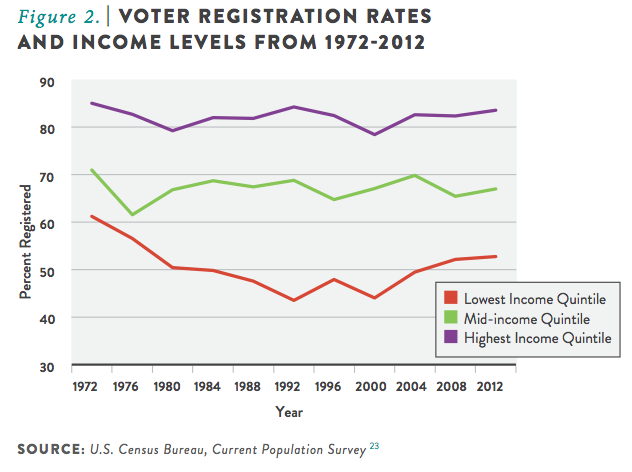

In general, as seen in the graph below, these registration difficulties contributed to overall voter registration rates steadily declining over time. Overall registration rates were lower in1992 than in 1972.

Unnecessarily confusing and complicated voter registration procedures particularly impact lower-income voters. According to U.S. Census data, unregistered individuals in households making less than $15,000 are twice as likely to say they are not registered because they do not know how or where to register as those making $75,000 or more.

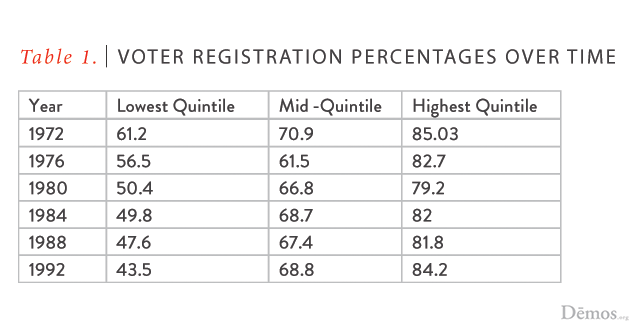

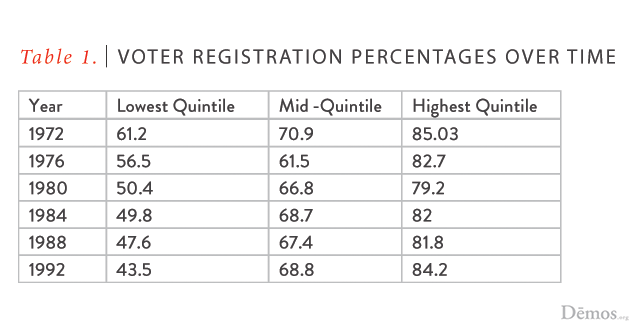

While overall registration rates declined, voter registration among the lowest income quintile declined markedly. The table below shows that from 1972 to 1992, voter registration among the lowest income quintile saw a nearly 18 point percentage drop – from 61.2 percent in 1972 to 43.5 percent in 1992. In contrast, the highest income quintile consistently had voter registration rates near or over 80 percent during the same period.

Prior to the NVRA, a lack of uniform voter registration availability across the states, low overall registration rates, and significant gaps in registration rates for various demographic subgroups meant there was a desperate need for reform at the national level.

The Success of the National Voter Registration Act

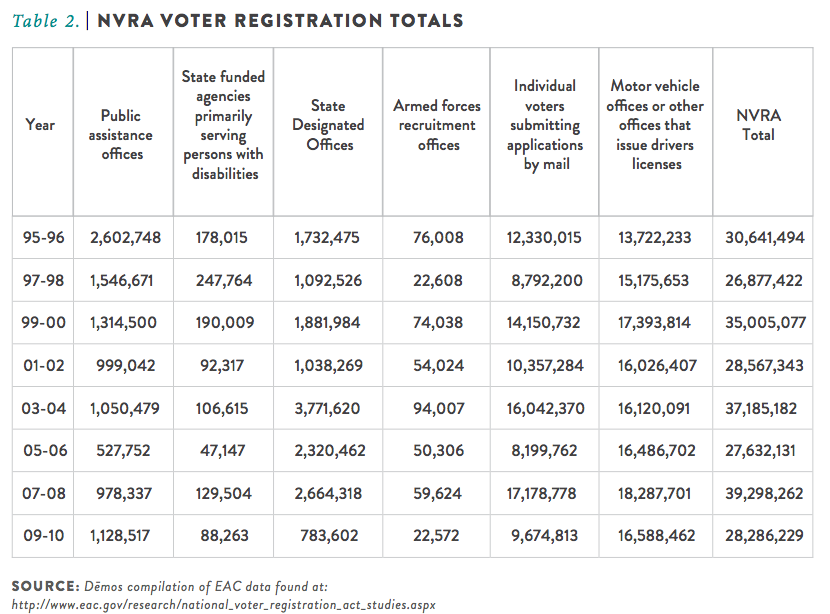

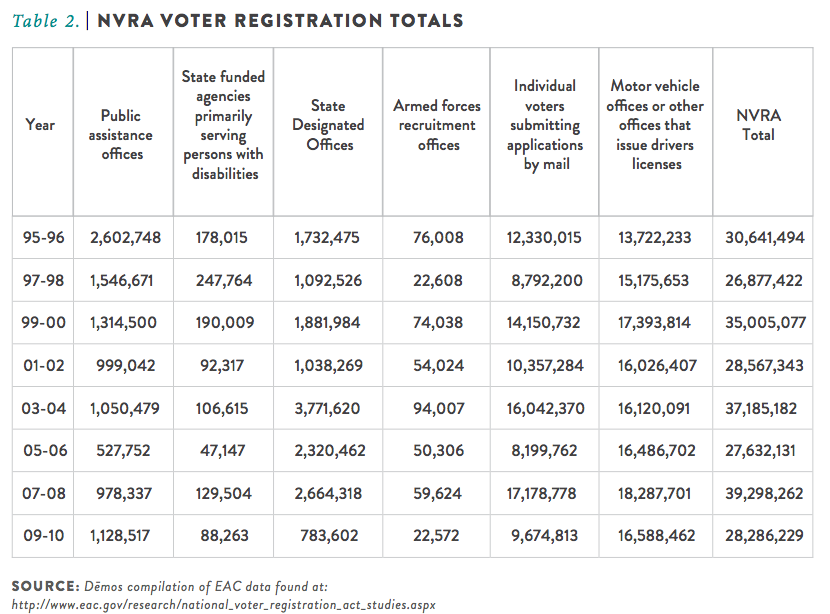

In its first year of implementation, as the table below shows, over 30.6 million people submitted voter registration applications or updated their registrations through methods made possible by the NVRA, either through offices including motor vehicle, public assistance, disability or armed forces recruiting offices, or by mailing in their voter application.

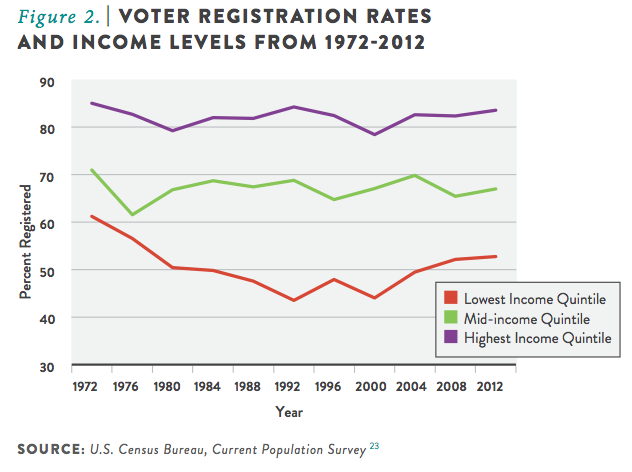

Year after year, the NVRA helps millions of eligible voters register. In particular, the NVRA has helped bring millions of low-income voters into the political process. In 1996, the first presidential election after the implementation of NVRA, voter registration among the lowest income quintile increased significantly, as shown in the graph below.

However, while the potential for increasing registration among low-income populations was great, the full promise of the NVRA was hampered by lackluster compliance and implementation. In particular, compliance with the NVRA’s requirements for registration through state public assistance and disability offices was poor after 1995.

After the initial surge of applications at public assistance offices, federal data show that the number of voter registration applications from public assistance agencies dropped by 79 percent between 1995-1996 and 2005-2006. Field investigations by Demos and its partners, along with evidence produced during litigation, revealed widespread noncompliance with Section 7 throughout the country. The lack of oversight and enforcement of Section 7 may have contributed to registration rates among the lowest income quintile remaining below 50 percent through the 2004 election.

Since 2004, Demos and its partners have used a combination of litigation and cooperative efforts to increase enforcement of Section 7. And, as detailed in the pull-out page, these efforts have been successful.

As shown earlier in Table 2, millions of individuals have registered to vote at public assistance offices since the NVRA’s enactment. The increase in voter registration among the lowest income quintile in recent years – reaching 52.7 in 2012, compared to only 43.5 percent in 1992- is encouraging. By providing voter registration through government agencies that serve low-income eligible voters, the NVRA is clearly helping make voter registration less cumbersome and more accessible.

Impact of Proper Section 7 Implementation

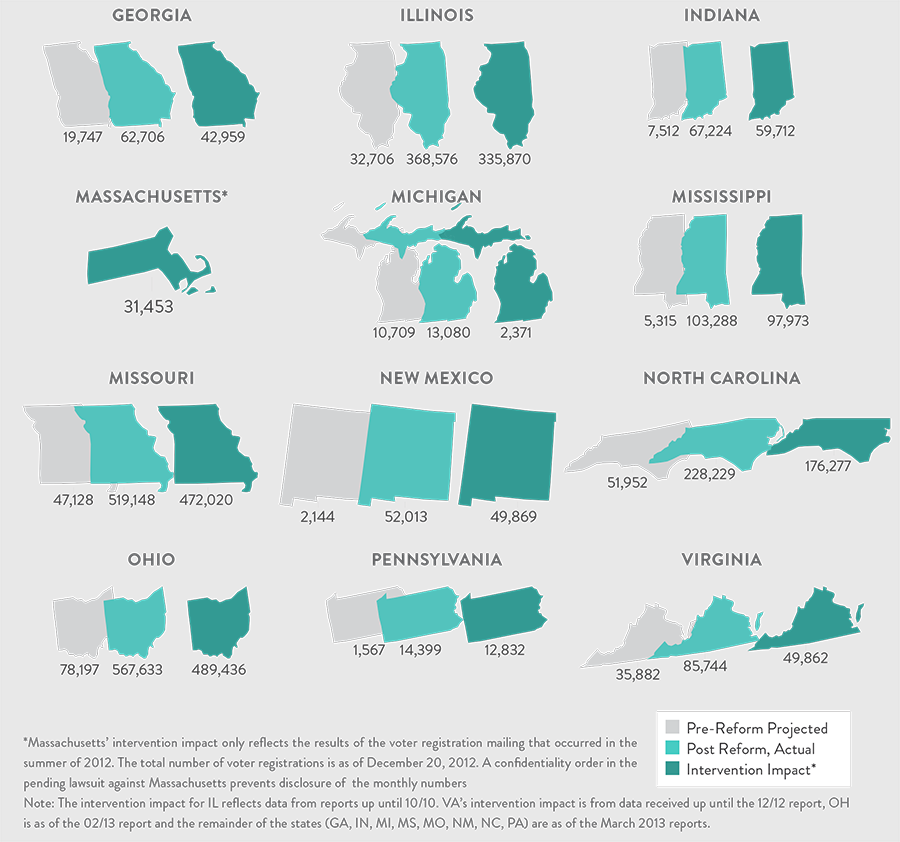

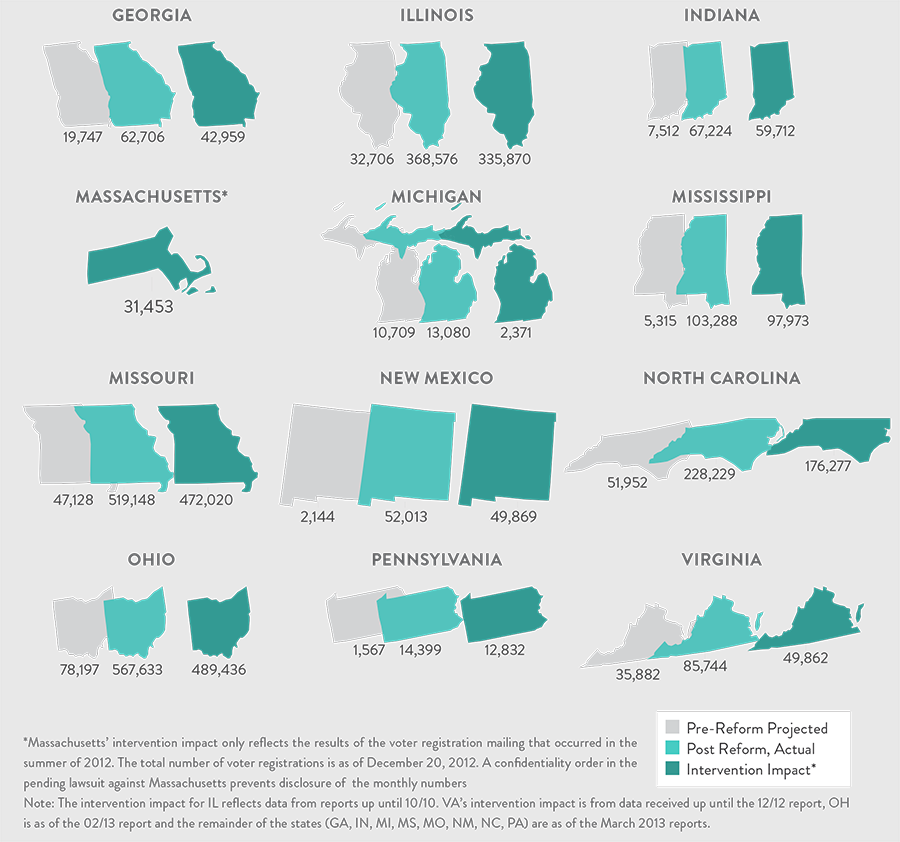

For the past several years, Demos and its partners have been working with state officials to properly implement Section 7 of the NVRA after finding that many states neglected their obligation to provide voter registration services to applicants and recipients of public assistance benefits. Since 2007, Demos’ work, which has included both litigation and cooperative work with state officials, has helped 1,820,633 eligible voters apply to register to vote at public assistance agencies. In the chart below, the first column is the number of voters projected to apply for voter registration at public assistance offices, had there been no intervention to increase enforcement of Section 7 requirements. The second column is the number of eligible voters that actually applied to register after Demos and its partners took action. The last column shows the net impact that enforcement of Section 7 has had in terms of increasing voter registration applications through public assistance offices.

Demos’ work is proof that when laws to protect peoples’ democratic rights are put into practice, they can have a major impact on bringing more voices into the political process. If more states follow suit, millions of additional lower-income Americans will have the opportunity to participate in our democracy in coming years.

The Next Era of NVRA and Voter Registration Policies

Undoubtedly, the NVRA has successfully registered millions of eligible voters. Yet, there is still work to be done. Voter registration rates are not as high as they could be, particularly among our lowest income citizens. Expanding the number of public agencies that offer voter registration services is a simple and necessary first step to engaging more eligible low-income voters. Ensuring proper implementation and enforcement of the NVRA is another necessary step towards fulfilling the true potential of the Act. Finally, despite the efforts of the NVRA, registration obstacles still exist and our voting systems need to be modernized in several ways.

Expanding NVRA to More Public Agencies

While the NVRA successfully brought millions of eligible voters into the political process, and the registration gap between low-income and high-income voters has narrowed in recent years, voter registration rates for the lowest income quintile are still well below those of higher income groups, indicating that targeted voter registration efforts towards these eligible voters is still necessary. In addition to continuing outreach to lower-income eligible voters, specific communities with low voter registration rates could be reached through expanding NVRA implementation in several key ways:

Indian Health Services: Nearly two out of five American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible to voter are not registered. Designating Indian Health Service (IHS) facilities as voter registration agencies would help ease barriers to registrations and could reach more than 1.9 million American Indians and Alaska Natives.

United States Citizenship and Immigrant Services: Naturalized Americans vote at rates significantly below native-born Americans. The voter participation gap between the two communities is parallel to the voter registration gap. For naturalized citizens who are registered to vote, turnout rates are comparable, or even higher, than registered native born citizens. Therefore, making voter registration more accessible is the key to increasing participation of naturalized citizens. Designating the United States Citizenship and Immigrant Services as a full voter registration agency would offer new Americans the opportunity to register to vote at all administrative naturalization ceremonies.

Affordable Care Act Health Benefit Exchanges: The new health care law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), provides an additional opportunity to register millions of new voters. Subsidized health insurance under the ACA – “Insurance Affordability Programs” – constitutes public assistance, so the NVRA’s requirement for providing voter registration services applies. Successfully integrating the NVRA voter registration requirements into the ACA Health Benefit Exchanges could provide up to 68 million additional eligible voters the opportunity to register to vote and thus to participate in our political process.

Expanding Enforcement of NVRA at Public Assistance Agencies

While Section 7’s requirement to provide voter registration at public assistance agencies has helped millions of eligible voters register, it has not reached its full potential. States must be diligent in ensuring that Section 7 procedures are being implemented properly. The following steps will help states implement effective NVRA plans:

- Appoint a State-Level NVRA Coordinator for Each Agency and Local Coordinators for Each Local Office—A state-level coordinator is needed to ensure that someone “owns” NVRA compliance and can ensure that voter registration services are in fact provided by frontline workers. A local NVRA Coordinator is needed in each local agency office to be accountable for ensuring administration of the NVRA in any particular office.

- Review Procedures to Ensure Voter Registration Policies and Procedures Are in Compliance with the NVRA—Many states may not have systematically reviewed their policies and procedures since 1995 when the NVRA first went into effect. Bringing these policies and procedures up to date is crucial to effective compliance.

- Regular Training and Easy Availability of Voter Registration Policies and Procedures to Front Line Agency Employees—Agencies (in conjunction with elections officials) should create standardized training materials, which should be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure they are accurate and up-to-date. All newly hired employees should be trained on voter registration procedures and current employees should receive refresher training at least annually, although some states’ implementing legislation requires training to be conducted more frequently.

- Adequate Supply of Voter Registration Applications and Voter Preference Forms for Each Office—Each public assistance office should ensure that it has at least a two-month supply of each form on hand (voter registration applications, voter preference forms, and any other state-specific forms).

- Use of Technology to Integrate Voter Registration Services into Covered Transactions—Computer technology comes into play in and streamlines many aspects of implementation of Section 7 at public assistance offices. Technology can be used in training programs. Computer-guided systems can guide interactions between frontline workers and clients during covered transactions. Such systems can easily collect voter registration related data. Importantly, as more benefits transactions are conducted online and through Internet-based systems, voter registration services must also be provided online.

- Implementation of a Comprehensive Oversight Program—Monitoring each office’s performance through frequent reporting of the numbers of voter registration applications and voter preference forms completed at each office helps to assess whether the procedures being implemented are effective and allows offices with low performance to be identified for remedial action.

While the need for the NVRA was clear, the act had to survive several legal challenges after it was first implemented. When it first passed, several states fought aggressively against implementation. California, Illinois, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, New York, South Carolina, and Virginia all refused to implement the NVRA or lagged in meeting the law’s full requirements, resulting in court actions where the validity or scope of the law was challenged. The federal courts uniformly upheld the NVRA and ruled that it was well within Congress’ power to improve citizens’ access to participation in federal elections.

Currently, a case is pending before the U.S. Supreme Court that could challenge the NVRA’s ability to create a uniform federal mail-in application for voter registration that all states should be required to accept under the NVRA. Arizona enacted a law to require documentary proof of citizenship to accompany any voter registration application, even when applicants have attested to citizenship under oath. This provision directly conflicts with NVRA procedures, which require states to accept and use a uniform federal mail-in application, and prohibit unnecessary obstacles to voter registration. If the court sides with Arizona, more states may seek to adopt such burdensome requirements, undermining the full promise of the NVRA,

Additional Policies to Expand Voter Registration

Each generation has the responsibility to meet new challenges to ensure that all eligible persons can exercise the freedom to vote. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had historically been used to disenfranchise African-American and other marginalized voters. In 1993, Congress passed the NVRA. Now, the time has come for the next generation of voting reforms. The following reforms would ease access to registration, save time and money, and bring millions of eligible voters into the political system.

Modernizing the Voter Registration System: Modernizing voter registration by replacing paper-based practices with electronic systems and procedures saves money, improves the accuracy of voter rolls, and streamlines bureaucracy. A modernized system would mean that an eligible voter’s information would be available in state databases that would allow appropriate government employees to access and manage the information or send it to another jurisdiction with minimal additional data entry and fewer administrative tasks. The Help America Vote Act (HAVA) already requires statewide voter databases, which is a step to creating the necessary infrastructure for modernizing all voter registration.

Same-Day Registration: Implementing Same Day Voter Registration (SDR), which allows eligible individuals to register and vote at the same time, is a proven method to increase participation and turnout among eligible voters. Three states- Maine, Minnesota, and Wisconsin- have offered SDR since the 1970s. Since that time, eight additional states- California, Connecticut, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Wyoming and the District of Columbia- have enacted the reform. In addition, as of this writing, Same Day Registration bills have just been signed by the Governors of Maryland and Colorado, and other states, including Delaware, are considering similar legislation.

States that provide SDR record consistently higher voter turnout and participation rates than states without it. Four of the top five states for voter turnout in the 2012 presidential election offered SDR, and the average voter turnout in SDR states was over 10 percentage points higher than in other states.

Making Registration Permanent and Portable: Almost 36.5 million US residents moved between 2011 and 2012. Low-income individuals are twice as likely to move as those above the poverty line. Voter registration should become portable and permanent for persons who move within a start through automatic updates to registration records as citizens change their address.

Conclusion

In the 20 years since the NVRA passed, voter registration has become more accessible. Newly registered voters do not remember a time when voter registration was not available through an array of government offices, as well as by mail. Despite attacks and challenges, the NVRA has successfully registered millions of eligible voters since its enactment 20 years ago. We must continue to protect and expand the freedom to vote. Looking forward, modernizing and expanding the NVRA, along with other voter registration reforms, will help eliminate registration gaps between communities and bring more voices into our political process. In doing so, our democracy will be stronger and more vibrant.

Appendix 1: Details of NVRA

The NVRA facilitated voter registration in three key ways: 1) by requiring state motor vehicles to offer voter registration; 2) by requiring public assistance and disability offices to offer voter registration; and 3) by requiring states to accept mail-in registration forms, including a uniform federal mail-in form.

Under Section 5 of the NVRA, every driver’s license application is simultaneously a voter registration application, unless the applicant does not sign the voter registration application. In addition, all changes of address submitted to state motor vehicle agencies must be forwarded to election authorities, unless the registrant chooses to opt out on the form.

Section 6 of the NVRA requires states to accept voter registration application forms by mail. States must accept and use a federal form created by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC), and may also develop their own form, as long as it meets all of the same criteria required by the NVRA for the EAC’s form. States must make the mail-in forms available at governmental and private entities. The forms are also available on the EAC’s website.

Under Section 7, any office that provides public assistance or state-funded programs primarily engaged in providing disability services must offer voter registration services. Section 7 also requires Armed Forces recruitment offices to provide voter registration services. States are also required to designate “other offices” as voter registration agencies, which may include state higher education facilities, public libraries, city and county clerk offices, and unemployment compensation offices.

Public assistance offices include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food-Stamp Program), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program (formerly the Aid to Families with Dependent Children or AFDC program), the Medicaid program, and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). It also includes state public assistance programs.

Disability services offices include, but are not limited to, offices providing vocational rehabilitation, transportation, job training, education counseling, rehabilitation, or independent-living services for persons with disabilities.

Section 7 also requires that each office designated as a voter registration agency must:

- distribute voter registration forms

- provide a form with information on the voter-registration process

- provide the same level of assistance to all applicants completing voter-registration forms as is provided with every other service or application for benefits

- accept completed voter registration forms

- transmit each completed application to the appropriate state election official within a set time frame.

The opportunity to register to vote must be given to people when applying for the agency’s assistance or services, seeking recertification or renewal of said services, and recording a change of address for the assistance or service.