Retailers put a great deal of resources into dealing with theft. They install security cameras, affix anti-theft tags to merchandise, and hire guards to protect stores. Signs warn that shoplifters will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. And yet another type of theft in the retail sector receives far less attention, even though it is equally, if not more pervasive in our economy: employers stealing pay they legally owe to their workforce.

Key Facts

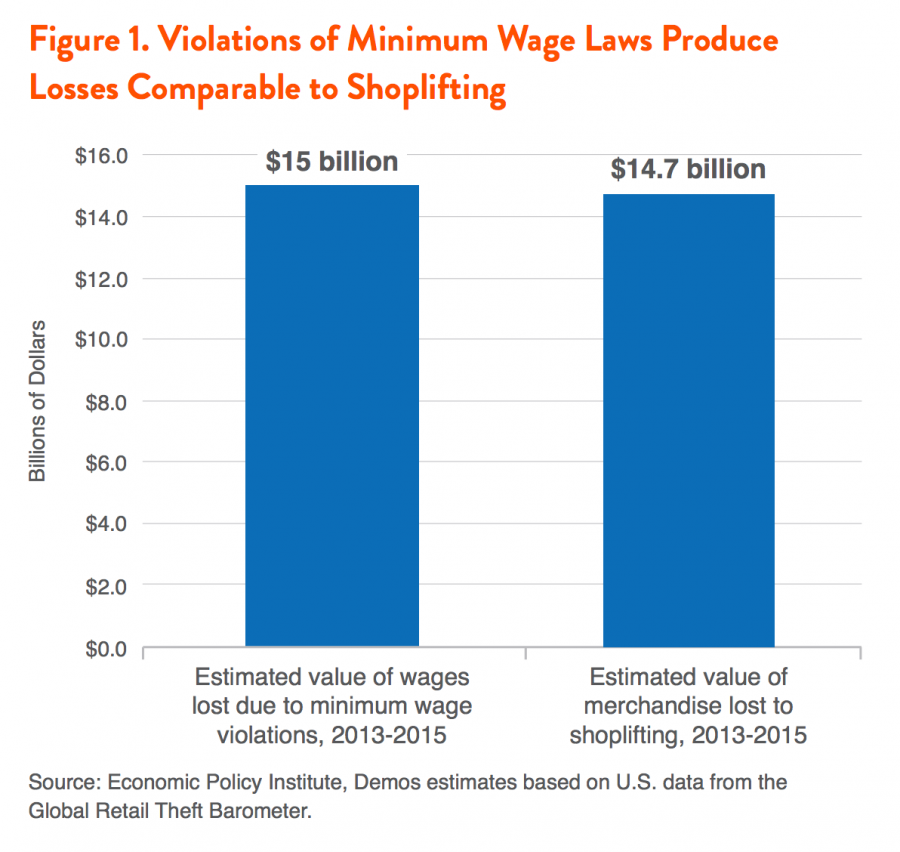

- Just one form of wage theft is equivalent to the value of all merchandise lost to shoplifting nationwide.

- By paying less than the legal minimum wage, employers steal an estimated $15 billion every year. This compares to an estimated $14.7 billion lost annually to shoplifting.

- Despite the pervasiveness of wage theft, retailers spent 39 times more on security than the entire Department of Labor budget for enforcing minimum wage standards.

- In 2015, retailers spent an estimated $8.9 billion on security. This compares to $227.5 million budgeted for the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division to enforce wage standards.

- Shoplifters can wind up in jail, but federal penalties for wage theft are not much of a deterrent—even when millions of dollars are stolen.

- If a shoplifter steals more than $2,500 in merchandise, they can face felony charges in any state in the country. The greatest civil federal penalty for wage theft is repaying the amount in stolen wages and an equal amount in liquidated damages. Even for repeat or willful violations, the maximum penalty is $1,100.

- Wage theft has disastrous consequences for workers, families, and the public.

- Minimum wage violations cut into the paychecks of an estimated 4.5 million working people and their families, and drive more than 302,000 families below the poverty line.

- In the retail industry alone, 358,000 workers are cheated by minimum wage violations.

Introduction

In a recent paper, the Economic Policy Institute calculated that employers steal $15 billion a year from workers’ paychecks by paying less than the minimum wage. As a result, hundreds of thousands of working families are pushed below the poverty line as large portions their paychecks disappear. Retail is one of the leading sectors for minimum wage violations. Yet the true scope of pay violations is far greater, both in retail and beyond: researchers find that requiring employees to work off-the-clock, work through meal breaks, or failing to adequately compensate employees for working overtime are even more widespread in the retail industry than minimum wage violations. Together these pay violations are known as wage theft.

This report compares the scope and impact of wage theft in the retail industry and beyond with the scale of shoplifting from retail stores. We aim to understand how and why these two types of misappropriation are treated so differently—even when both occur in a retail setting. We look at the resources devoted to stopping violators and the penalties for violating the law. We find that a retailer that steals millions of dollars in wages from its employees often faces a low risk of punishment and a far lighter penalty than the shoplifter who nabs a pair of shoes off its shelves. When corporations violate the nation’s core wage laws, working Americans are pushed into poverty, cities and states are robbed of tax revenue, and law-abiding businesses are put at a competitive disadvantage. While the consequences of wage violations can have a devastating impact on the lives of working people, companies know they are unlikely to be caught and that any penalties imposed will be mild. As a result, unscrupulous employers realize that the reward of stealing wages is greater than the risk. Far greater resources for investigation and enforcement and strengthened penalties for violations are needed to curtail wage theft.

We conclude that the disparity in resources and penalties for shoplifting compared with wage theft has little relationship to the pervasiveness or seriousness of harm associated with the violations, and more to do with larger inequities in our society and legal system. Wage theft is an offense committed by more powerful entities (employers, including large corporations) against the less powerful (workers). Members of economically and socially vulnerable groups (including women, people of color, and immigrants, especially undocumented workers) are disproportionately likely to be victims of wage theft. When it comes to shoplifting, people of color, particularly African American consumers, are disproportionately likely to be profiled as potential shoplifters, even as experts assert that there is no “typical” shoplifter. Reforming a justice system tilted in favor of power and privilege requires efforts to eliminate retail profiling and racial bias in the criminal justice system as well as a far greater focus on the crimes of the powerful, including wage theft.

What is wage theft?

Wage theft occurs when an employer pays workers less than they are legally owed for their work. It is typically a violation of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act or of state or local law. Examples of wage theft include paying less than the minimum wage, stealing employee tips, failing to pay overtime, requiring employees to work through required meal or rest breaks, forcing workers to work off-the-clock, or making illegal deductions from paychecks. In some cases, workers are never paid at all. Because wage theft is dramatically underreported, it is notoriously difficult to measure. In many cases workers may not know or understand their full rights on the job. Even when workers know they are being cheated by an employer, they may not know how to report the violation or may fear being fired or subject to some other form of retaliation if they speak up.

Yet without reporting, it is difficult to know when wage theft occurs. Recently the Economic Policy Institute released a rigorous study drawing on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey to estimate the extent of one type of wage theft—the failure to pay workers at least the minimum wage—in the nation’s 10 most populous states. The study uses averages of data from 2013 through 2015. The states of California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas represent 53 percent of the nation’s workforce and can be reasonably generalized to the country as a whole. This study is our primary source of data on the prevalence of minimum wage violations. We also look at back wages reclaimed by the Department of Labor’s wage and hour division, the nation’s primary federal enforcement body for wage theft violations.

What is shoplifting?

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook defines shoplifting as “the theft by a person (other than an employee) of goods or merchandise exposed for sale. By definition, the offender in a shoplifting incident has legal access to the premises and, thus, no trespass or unlawful entry is involved.” The FBI collects statistics on shoplifting and other crimes reported to local police departments. However, not all cases of shoplifting are reported, either because perpetrators are not apprehended or because retailers opt not to involve the police. To estimate total annual losses due to shoplifting, this report relies on United States data from the Global Retail Theft Barometer produced by research and analytics firm Smart Cube. This data is averaged from 2013 through 2015 to match estimate years for wage theft. We also draw on National Retail Federation’s annual National Retail Security Survey to estimate retailers’ spending on security measures in 2015.

Failure to pay minimum wage—just one type of wage theft—is as prevalent as shoplifting.

Stealing is wrong. This is a fundamental idea in our society and economy. But while taking merchandise from a store—shoplifting—is widely condemned, there is much less awareness of employers cheating workers out of the wages they are owed. This disparity is not because wage theft is less widespread. We find that just one form of wage theft, the failure to pay minimum wage, is as prevalent as shoplifting. A recent study of minimum wage violations (see “What is Wage Theft” ) finds that employers steal $15 billion annually from their employees by paying them less than the legal minimum wage and pocketing the difference. The study uses data averaged from 2013 through 2015. During that same period, as Figure 1 shows, the Global Retail Theft Barometer claims $14.7 billion was lost to shoplifting in the United States, including losses to both casual shoplifters and organized retail crime rings. In other words, cheating the lowest-paid employees in the nation out of the minimum pay they are due by law is as widespread as stealing from the shelves of a store.

Failure to pay minimum wage is particularly prevalent in the retail sector. Retail workers lose an estimated $1.4 billion every year as a result of employers’ failure to pay minimum wage. Yet it isn’t even the most prevalent form of wage theft in retail: a study of low-wage workers in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago found that 25.7 percent of retail and drugstore employees experienced a minimum wage violation in the past week; however, other forms of wage theft (such as failure to pay overtime, requiring employees to work off-the-clock, or mandatory work during meal breaks) were far more common. A survey of retail employees in New York City suggests that violations of the state’s reporting-pay law—mandating that employers pay workers for a minimum four-hour shift even if they are sent home early—are also common. If the full scope of wage theft was measured, it would be far greater than the amount lost to shoplifting.

Far fewer resources are devoted to enforcing wage laws than to preventing theft from retailers.

In 2015, retailers spent an estimated $8.9 billion on security and other “loss prevention” efforts, according to data from the National Retail Federation. Stores frequently used surveillance cameras and burglar alarms, and many employed or contracted their own security personnel dedicated to deterring would-be shoplifters and apprehending offenders. The total does not include the public resources such as police, court systems, and jails devoted to apprehending, prosecuting and punishing suspected retail thieves. And yet, as Figure 2 illustrates, retailers’ spending on their own security is 39 times greater than the entire amount the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division budgeted for enforcing minimum standards for wages and working conditions throughout the U.S. economy in 2015.

The enormous disparity in funding corresponds to predictable differences in personnel: data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that 43,930 security guards are employed in the retail sector, guarding, patrolling, or monitoring premises to prevent theft, violence, or infractions of rules. This figure does not include the other retail employees—from fitting room attendants at a clothing store to convenience store clerks—who are expected to play a role in preventing shoplifting, nor does it encompass thousands of public police officers whose responsibilities include preventing and investigating shoplifting. Meanwhile, the Department of Labor employed approximately 1,000 investigators tasked with enforcing wage laws for 7.3 million U.S. workplaces and 135 million workers. In some states, state labor department and attorneys-general supplemented the federal effort to enforce wage laws, but their resources were even less. As hard as Wage and Hour division staff worked—completing 27,915 compliance actions in 2015, and obtaining agreements to pay over $246 million in back wages to workers—they lacked the personnel and resources to match either the deterrent effect or the enforcement power of the security apparatus arrayed against shoplifters, as shown in Figure 3.

Shoplifters can wind up in jail, but federal penalties for wage theft are not much of a deterrent, even when millions of dollars are stolen.

If a shoplifter steals more than $2,500 in merchandise, they can face felony charges in any state in the country. In Virginia and New Jersey, theft of merchandise worth as little as $200 can bring a felony conviction and jail time. And in many states, retailers can also sue shoplifters for civil damages on top of the criminal penalties they will face.

In contrast, federal criminal penalties are almost never applied to employers who steal wages, even if tens of thousands of dollars are systematically misappropriated from hundreds of employees for months or years. The civil penalties under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act are too weak to act as an effective deterrent. At most, the Department of Labor can recover only the amount by which the employer failed to pay employees the legal minimum, plus an equal amount in liquidated damages. Even for repeat or willful violations, the maximum penalty is $1,100. For first-time offenders or cases where a violation cannot be proven to be willful, the law imposes no penalty at all.

Consider the case of furniture retailer Han Nara, which operates 7 stores in Texas, Washington State, and New Mexico under the name Ashley Furniture Home Store. The Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour division investigated the retailer 4 times over 9 years, each time finding that it had failed to pay its employees properly. After 2 sets of investigations and fines in 2010, the Department of Labor found in 2011 that 170 current and former employees of Han Nara had been cheated out of more than $57,000, and ordered the company to pay back wages.Yet the repeat investigations and slap-on-the-wrist fines failed to provoke any change in the retailer’s practices, as hundreds of employees were repeatedly cheated of the minimum pay they had worked for and were owed. Han Nara didn’t stop stealing from its workers: in 2016, the company was again found to have cheated more than 500 employees out of their paychecks. From the company’s point of view, it was apparently cheaper to pay repeat penalties to the Department of Labor than to properly compensate employees.

Weak penalties and a lack of resources for public enforcement leave working people who are victimized by wage theft with one option: going to court in an effort to recover their stolen pay. Yet increasingly, this avenue for seeking justice is also closed off for retail employees. Many major retailers, from high-end department stores Nordstrom and Neiman Marcus to fast-fashion mainstay Forever 21, now mandate that employees sign forced arbitration agreements curtailing their ability to sue the company over workplace disputes and often banning participation class action lawsuits. Under forced arbitration agreements, workers must agree to resolve any future legal claims against the company through a binding arbitration process. This process strongly favors employers, who are far more likely to prevail in arbitration than in state or federal court. There is no transparency or precedent in the process, and workers have little opportunity to appeal an unfavorable decision. The arbitration process can also be costly for workers, who may be required to share the cost and sometimes even cover their employer’s legal fees. This privatized system of justice, designed by and for employers, replaces the public system which retains at least the ideal of equality before the law, mirroring the privatized criminal justice system that confronts shoplifters at Walmart and many other retailers (see “Wage Theft and Shoplifting at Walmart”).

The consequences of wage theft are disastrous for workers, families, and the public.

Retailers emphasize that shoplifting is not a victimless crime: retail profits take a hit and higher costs are passed on to customers. Taxpayers bear the cost of law enforcement responses to shoplifting. Yet these costs pale in comparison to the consequences of wage theft, which pushes families into poverty, forces working people to rely on public benefits to make ends meet, and robs states and cities of needed tax revenue. Businesses that comply with the law may face a competitive disadvantage from rivals able to cut prices because they are cheating employees. Spread over millions of workers subjected to wage theft, the social costs are staggering.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates that 4.5 million working people across the country are victims of wage theft every year. Workers exposed to minimum wage violations lose an average of nearly one-quarter of their already low incomes to employer theft. As a result, many working people and their families are pushed into poverty: in the nation’s 10 most populous states, minimum wage violations throughout the economy forced 160,000 workers and their families below the poverty line. On a national basis, this would amount to more than 302,000 families driven into poverty as a result of minimum wage violations.

In the retail industry alone, an estimated 358,000 working Americans are victimized by minimum wage violations each year. On average, they lost a sixth of their annual pay, equivalent to $2,100 stolen from their family’s income for the year. Yet as we’ve noted previously, violations of minimum wage laws are not the most common type of wage theft in the retail industry—workers and their families are even more likely to be affected by overtime violations, being obliged to work off-the-clock, and other workplace violations. The full impact of wage theft in retail remains incalculable.

Workers and their families feel the greatest and most immediate effects of wage theft; when families see low incomes depressed even further, it affects workers’ health and the wellbeing of children. A growing body of research looks at the lifelong impacts of growing up in poverty on the education and life chances of children. At the same time, families pushed closer to poverty are compelled to rely on public benefits such as food stamps (SNAP benefits) in order to feed their families. While employers violate the law, the public must step up to feed their employees. Wage theft also takes a toll on local, state, and federal tax revenue. In a study of minimum wage violations in New York and California, the Department of Labor quantified lost tax revenue, including $283 million to $343 million in lost payroll tax revenue and $112.7 million in lost federal income tax revenue in these two states alone in 2011.Nationwide, this would amount to as much as $2.5 billion in lost payroll and income tax revenue due to violations of minimum wage law, $429 million as a result of minimum wage violations in the retail industry alone.

Wage Theft and Shoplifting at Walmart:

Stolen Pay vs. Suspected Shoplifting at the Nation’s Largest Employer

Nowhere is the contrast between attitudes toward shoplifting and wage theft more apparent than at Walmart. The retail giant is the largest private employer in the United States, and it may well be among the nation’s largest perpetrators of wage theft. Walmart fights allegations of wage theft vigorously, delaying justice for years. Meanwhile, the company has faced numerous allegations of racially profiling black and Latino shoppers as suspected shoplifters. At many Walmart locations, accused shoplifters are pushed into privatized, for-profit programs that, according to one pending lawsuit, “intimidate and extort the accused.”

Courts ruled that between 1998 and 2006, Walmart forced 187,979 employees in Pennsylvania to work off the clock and skip meal breaks, with the company saving more than $49 million by not paying workers what they were owed. The pressure to work without pay became worse during the holidays, former Walmart employee Delores Killingsworth Barber testified, when workers were required to do “whatever it takes to get done, and if that meant missing your break, [and not being paid for it] that’s what had to be done.” Yet Walmart’s army of attorneys fought the case all the way to the Supreme Court. It was not until the Supreme Court denied Walmart’s final appeal in 2016, after 14 years of complaints, investigations, and appeals, that the way was finally clear for Walmart workers to receive compensation that had been stolen from them a decade or more ago.

A similar pattern emerges around the country. Whether one looks at the case of 1,800 workers employed at 3 of Walmart’s Southern California warehouses who ultimately won $21 million in unpaid wages, interest and penalties for failure to pay overtime and other wage violations, or at the 900 Walmart delivery truck drivers denied the minimum wage, it is apparent that a company with ample resources to understand and obey basic wage laws nevertheless flouts them, and fights workers’ resulting legal claims to the bitter end.

Accused shoplifters face very different treatment. Corrective Education Company (CEC), a private firm handling security for a number of major retailers, including many Walmart locations, is under fire for “extorting suspected shoplifters into paying hundreds of dollars to participate in its six-hour-long behavioral modification program or face criminal prosecution,” according to a pending lawsuit by the San Francisco City Attorney. “After making false and misleading statements… designed to distort the choice facing accused shoplifters and boost the likelihood that they will… ‘choose’ to participate in the program, which forces them to sign unlawful contracts confessing to crimes. If they are unable to pay, CEC threatens to hand the case over to police for prosecution.” As one attorney pointed out, “There’s no judicial oversight, there are no constitutional protections, there’s no due process. It’s a private company acting as prosecutor, judge, jury, and collector.” Walmart and other retailers that contract with CEC and its competitors often receive a cut of the proceeds from the fines suspected shoplifters pay, creating an incentive to pressure people to enroll regardless of any evidence of guilt. As customers who may never have stolen a thing struggle to pay back fees for a privatized justice program, Walmart’s attorneys fight for years against repayment of millions of dollars in stolen wages.

Conclusion

This comparison of the prevalence of shoplifting and wage theft reveals that the losses from one single type of wage theft—violations of minimum wage law—are as great as the entirety of shoplifting losses reported by the Retail Theft Barometer. Both amount to billions of dollars annually. In the case of wage theft, these losses strike at the most vulnerable working people, pushing hundreds of thousands of working Americans into poverty. Yet wage theft, an offense committed by the powerful against those with far less power, receives a fraction of the deterrence, investigatory, and enforcement resources devoted to shoplifting. Penalties are also disproportionate: shoplifting carries a criminal penalty, even a felony conviction if the value of goods stolen is substantial enough, but civil penalties for wage theft are mild, including fines that are too low to be an effective deterrent.

In 2016, Senators Patty Murray and Sherrod Brown and Rep. Rosa DeLauro introduced the Wage Theft Prevention and Wage Recovery Act to Congress. The bill would compensate victims of wage theft with triple back pay; substantially increase civil fines, particularly for companies that are repeat offenders; allow employers to be referred for criminal prosecution in certain egregious cases; strengthen whistleblower protections; and make it easier for workers to take action to recover stolen wages. Combined with an expansion of resources for investigation and enforcement in the Department of Labor, this would help to address the epidemic of wage theft. Yet passage of this national legislation appears highly unlikely in the current political climate, and wage enforcement resources at the Department of Justice are likely to face cutbacks, not the needed expansion. Across the country a number of state and local governments have stepped up, increasing investigation and enforcement resources, engaging in public education so that workers know their rights and employers are aware of their responsibilities, and increasing penalties for wage theft. In California, another promising state-level policy enables workers to initiate wage enforcement actions on behalf of the state Attorney General or State Department of Labor. Federal, state, and local action is needed to ensure that companies in the retail sector and beyond do not feel free to rob their workforce with impunity.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Daniella Medina, Connie Razza, and Stuart Naifeh (Demos); David Cooper (Economic Policy Institute); Randy Parraz and Amy Ritter (United Food and Commercial Workers); and Kate Hamaji and Rachel Deutsch (Center for Popular Democracy) for invaluable advice and assistance with this brief.