More than two years after the recession officially ended, 25 million Americans – 16 percent of the labor force – are still out of work or underemployed.1 There are more than four jobseekers for every job opening. 6.2 million people have been out of work for more than six months. While the economic consensus is that federal stimulus measures prevented an even greater loss of jobs and a more severe downturn,2 these actions were clearly inadequate. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office projects that with current policies in place, it will take until 2016 to return to pre-recession employment levels.3 In short, the nation has a severe and persistent jobs deficit that will not be corrected simply through the workings of the market.

Persistent unemployment deepens existing inequalities, causing long-lasting harm to an individual’s future job prospects4 and making it harder for disadvantaged workers to ever work their way into the middle class. Population groups that are disproportionately unemployed – including people of color and Americans without a college education – suffer a far greater share of the long-term damage. Young people who are out of work also bear a greater long-term burden: even when employment rebounds, young adults will have more difficulty finding a job where they can reach their productive potential if they lack experience and professional networks built in their early working lives. For this reason, our jobs plan places priority on unemployed young people.

The jobs deficit is also an obstacle to the economy’s overall recovery. While large-scale job loss was initially a result of the recession, it has become a self-reinforcing drag on economic growth. With so many people out of work, consumer spending remains sluggish and the housing market and construction industry cannot rebound. At the same time, businesses won’t see it as profitable to invest and hire more workers in the United States until consumer demand picks up. With no strong private-sector source of growth on the horizon, the jobs deficit provokes a vicious cycle that will keep unemployment high for years to come unless the dynamic is altered by decisive government action. Using public employment to create jobs for the unemployed directly and immediately is the most effective way to disrupt the cycle, accelerating economic recovery and giving those hardest hit by the recession what they need most – an opportunity to work.

Policy Design

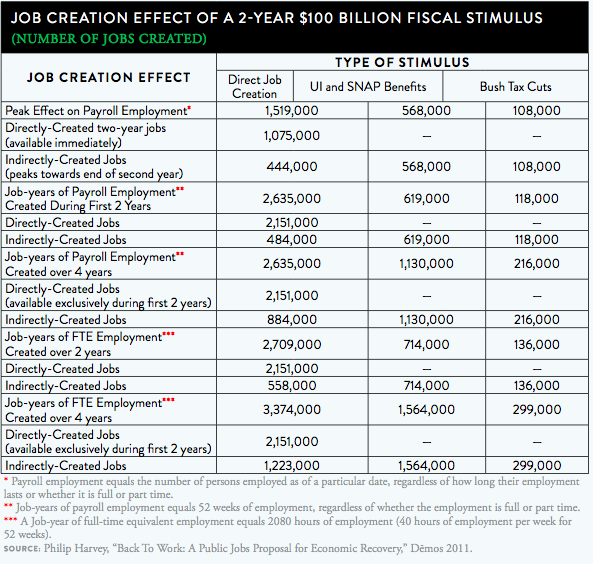

In a paper for Demos, economist Philip Harvey makes the case that a direct and immediate public jobs program would produce substantially more job creation for each public dollar spent than conventional fiscal stimulus measures such as tax cuts and public spending increases.5 A $100 billion, two-year public jobs program would create more than 1.5 million new jobs at peak employment, compared to 568,000 jobs created by a comparable increase in spending on unemployment insurance and food stamps, or just 108,000 jobs created by Bush-style tax cuts of comparable size.6

As Harvey explains, this strategy “also allows the government to offer work where it is most needed and to those individuals who most need it. Finally, it allows these jobs to be made available to people immediately, when they need them, rather than requiring them to wait for the economy to recover before they can put their lives back on track.”7

We propose investing a net $235 billion in the first year and $147 billion in the second year of a two-year public jobs program. This would create 8.2 million direct and indirect jobs, sufficient to reduce the nation’s unemployment rate to a pre-recession 4.5 percent. The program could be funded through the expiration of the Bush tax cuts (approximately $295 billion per year). The program design is described below.

- The program would create jobs for unemployed Americans addressing unmet needs in the communities where they live. The program should thus be targeted to states, cities, and communities with the highest unemployment rates, and should offer priority to young adults.

- Federally funded jobs could include rehabilitating and weather-proofing housing, improving public buildings and parks, building affordable housing, providing child care and elder care, teaching preschool in communities where these programs are not currently offered and staffing after-school and tutoring programs.

- Program participants would be paid at prevailing wages and benefits for employees with similar qualifications and would enjoy the same rights as other workers.

- The jobs program would be administered by the federal Department of Labor based on work categories and projects suggested by local governments.

- To ensure that total employment is increased, monitoring and safeguards would be implemented to ensure that the new public jobs are not used in ways that replace existing public workers or private contractors, since this would simply substitute program jobs for other jobs.

- The cost would be a net $235 billion in the first year and $147 billion in the second year of a two-year public jobs program.

|

View all policies

Endnotes

-

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation Summary,” U.S. Department of Labor (February 2012). http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm

-

Paul Wiseman and Barbara Hansen, “Exclusive: Obama stimulus reduced our pain, experts say,” USA Today, January 25, 2010, Accessed March 4, 2012, http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/2010-01-25-usa-today-economic-survey-obama-stimulus_N.htm

-

“Budget and Economic Outlook,” Congressional Budget Office (January 2011). http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=12039

-

Katherine S. Newman and David Pedulla, “An Unequal-Opportunity Recession,” The Nation Online, July 19, 2010, Accessed March 4, 2012, http://www.thenation.com/article/36883/unequal-opportunity-recession

-

Phillip Harvey, “Back To Work: A Public Jobs Proposal for Economic Recovery,” Dēmos (March 2011). http://www.Demos.org/pubs/BackToWork.pdf

-

Harvey, “Back To Work,” March 2011. http://www.Demos.org/pubs/BackToWork.pdf

-

Ibid. http://www.Demos.org/pubs/BackToWork.pdf

-

Hart Research Associates, “Tracking the Recovery: Voters’ Views on the Recession, Jobs, and the Deficit,” Economic Policy Institute (2009). http://www.epi.org/publication/tracking_the_recovery/