In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Americans battered by job loss, foreclosure, and plummeting home values tightened their belts and paid down debt. The Latino community, hit particularly hard by the housing crash, was no exception. Yet new research from Demos’ National Survey on Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income Households finds that even as Latinos are carrying less credit card debt, four in ten Latino households with credit card debt are relying on their cards to pay for basic living expenses. This study explores the use of credit cards and the impact of debt on Latino households in the wake of the Great Recession.

Among low- and middle-income households with credit card debt:

- Latino households are carrying less credit card debt, but many still depend on credit cards to pay for basic living expenses.

- Latino households that have credit card debt owe less than they did in 2008, carrying an average balance of $6,066 in 2012, compared to $8,661 in the 2008 Demos survey. This drop in credit card debt mirrors a decline in the indebted population as a whole.

- Similar to white and African American households, 43% of Latinos report using their credit cards to pay for basic living expenses such as rent, mortgage payments, groceries, utilities or insurance in the past year because they did not have enough money in their checking or savings accounts

- Latino households are less likely to report having insurance coverage than the population as a whole, and are more likely to say that medical costs contributed to their credit card debt.

- 49% of Latino households carrying credit card debt report that they or someone in their household has been without medical insurance in the last three years, compared to 34% of the population as a whole. Latinos are also more likely to report that they are currently without health insurance.

- In addition to being more likely to be without health insurance, Latino households are significantly more likely than other households with credit card debt to report that medical expenses such as hospital stays and the cost of prescription drugs contributed to their credit card debt.

- Unemployment is a leading contributor to credit card debt for Latino households.

- 19% of Latino households report that a layoff or the loss of a job was the greatest contributor to their overall level of credit card debt, compared to 15% of the indebted population as a whole, a difference that is not statistically significant.

- Among Latino debtors who experienced the loss of a job in their household, 87% said the job loss contributed to their debt.

- Latinos are more optimistic about paying down their credit card debt quickly than the population as a whole.

- 24% of Latinos say their credit has improved a lot over the last three years, compared to only 9% of the overall population

- 53% of Latino households predict they will be completely out of credit card debt in six months, compared to 43% of the overall population.

- The most common ways that Latino households report paying down credit card debt include using a tax refund, working extra hours or getting an additional job, drawing on savings, and borrowing money from family or friends.

- The CARD Act provides new protections to Latino borrowers.

- 38% of Latino households say new disclosure information as a result of the CARD Act has caused them to pay more toward their credit card balance in the typical month.

- 41% of Latino households report they have been charged late fees less often as a result of the CARD Act, compared to 26% of households overall. This suggests that Latino credit card holders are among the biggest beneficiaries of the act.

Introduction

Years after recovery from the Great Recession officially began,1 millions of Americans still confront unemployment, reduced incomes, and a massive loss of household wealth. Latino communities, which were targeted for high-risk mortgage loans and had much of their wealth invested in their homes, were hit particularly hard by the bursting of the housing bubble.2 According to data analyzed by the Pew Research Center, Latino families lost a staggering 67 percent of their total wealth during the housing crisis, compared to a loss of just 12 percent for white families.3 This tremendous loss of wealth only compounds the extreme wealth gap for Latino households that existed before the Great Recession.

In a difficult economy, many families struggle to sustain a decent standard of living. When the roof leaks or a child needs emergency medical care, households living on a tight budget may dig into their savings or draw on other assets to make ends meet. Yet Latino households often have fewer assets to fall back on than many other Americans, with Latinos reporting a median net worth of just $7,843 in 2011 compared to $91,405 for white households.4 With fewer resources to turn to, it stands to reason that low- and middle-income Latino households with access to credit cards have borrowed to make ends meet: our study finds that four out of ten low- and middle-income Latino households with credit card debt report using their credit cards to pay for basic living expenses because they did not have enough money in their checking or savings accounts. For many Latino families, as with other low- and middle-income American households, credit cards became a “plastic safety net”—used to make up for stagnant income, lack of private assets, and the failure of public safety net programs such as unemployment insurance, food stamps, and Medicaid to adequately cover the needs of the nation’s population.

At the same time, access to credit on fair terms has itself been a historic challenge for the Latino community. For example, the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances found that in 2004 three-quarters of American households overall used credit cards.5 Yet among Hispanic households, just over half (54%) reported using credit cards that year. One reason for the reduced access to credit may be a lack of pre-existing credit history that would allow households to qualify for cards. Recent Latino immigrants, for example, may be “thin file” consumers, lacking prior credit history and may thus be regarded as risky borrowers who are given access to only high-interest, subprime credit products. These products, in turn, may carry such high interest that it becomes difficult or impossible for households to keep up with the payments—resulting in worse credit and the loss of household wealth observed in the housing crash. With such limited options before them, it is understandable why many Latino households express reluctance to take on debt and concern about the use of credit cards.6

Yet the credit landscape for American households as a whole has also changed as a result of the Great Recession and the financial crisis. In the 2010 and 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances, the proportion of households using credit cards was down to 68 percent, a drop of approximately 9 percent from the years before the crash.7 The proportion of Latino households using credit cards experienced a similar decline, dipping below 50 percent. The drop represents both a tightening of credit access by financial institutions and a tendency of American households to discharge and pay back debt. For Latino households seeking to build a credit profile and access better financial opportunities, reduced access to credit is a negative trend. At the same time, the fact that Latino households with credit card debt, like their non-Latino counterparts, report lower credit card balances is a positive sign that cardholders are paying down debt and incurring lower interest charges as a result. The 2008 Credit CARD Act, which provided new protections for consumers and particularly benefitted Latino cardholders, offers another bright spot in the credit card landscape.

This report draws on Demos’ 2012 National Survey of Credit Card Debt Among Low- and Middle-Income Households to explore credit card trends in the Latino community in greater depth. The nationally representative 2012 survey follows two previous Demos surveys, conducted in 2005 and 2008. Details about the methodology of the survey, and the Latino sample, are in the following sections of this report.

Methodology

In February and March of 2012, Demos and GfK Knowledge Networks conducted a nationally-representative survey of 1,997 households, including 997 households who had carried credit card debt for more than three months and 1,000 households who had credit cards but no credit card debt at the time of the survey. The survey was offered in Spanish as well as English to all households. For our survey, moderate-income is defined as a total household income between 50 percent and 120 percent of the local (county-level) median income. All of our respondents were at least 18 years of age. In order to ensure that the indebted sample captures households who carry credit card debt, as opposed to those carrying a temporary balance, we only included households who reported having a balance for more than three months. The margin of error for the total indebted sample is +/- 3.9 percentage points.

An additional sample was used to obtain reliable base sizes for African American and Latino populations. The margin of error for the oversample of 152 African American households is +/- 11.3 percentage points. The margin of error for the oversample of 205 Latino households is +/-9.1 percentage points.

Demographics of the Latino population surveyed

Our survey aimed to have a representative sample of Latino households with credit card debt. This population differs slightly from the overall Latino population nationwide.8 In general, Latinos in our sample of households with credit card debt tend to be significantly older, with higher rates of marriage, parenthood, and homeownership and slightly higher incomes than the Latino population as a whole. One explanation for these divergences may be the time it takes to build up a credit history sufficient to be approved for a credit card and accumulate debt. As a result, it is logical that Latinos who have accumulated credit card debt tend to be older and better established than their counterparts with no credit card debt.

- Age: The median age in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt was 41.8 years. This is significantly older than the median age of the nation’s Latino population in general, which was 27.7 years in 2012.

- Income: the median household income in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt was $43,110—slightly higher than the $40,417 median household income for Latinos as a whole in 2012. A detailed income breakdown of our sample is as follows:

- 45% made less than $35,000 a year

- 49% made $35,000-$75,000 a year

- 6% made more than $75,000 a year

- Homeownership: in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt, 66% were homeowners, while 33% rented their homes. This is a significantly higher homeownership rate than the nation’s Latino population in general, which included 46% homeowners and 54% renters.

- Marital status: in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt, 66% were married and 33% were single. This is a significantly higher marriage rate than the 43% of the nation’s Latino population as whole that is married.

- Children: 56% of respondents in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt had children at home, compared to 47% of the nation’s Latino population as a whole.

- Education: 14% of respondents in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt are college graduates, a number statistically identical to the nation’s Latino population as a whole.

- Employment: 67% of respondents in our sample of Latinos with credit card debt reported that they were currently employed, a slightly higher proportion than the 60% employment rate of the nation’s adult Latino population as a whole. Note that in both our sample and the population as a whole, those who report they are not employed include retirees, homemakers, students, and people with disabilities that prevent them from working as well as people who are officially “unemployed” and looking for work.

Credit card basics for Latinos: balance, APR, and getting by on debt

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Americans battered by job loss, foreclosure, and plummeting home values tightened their belts and paid down debt. According to data from the Federal Reserve, average credit card balances fell significantly in the three years following the financial collapse. But the trend toward household deleveraging is only part of the story: even as consumers paid down their balances, this study finds that many moderate income households continue to rely on credit cards to make ends meet.

The broad trend among Latino credit card holders reflects that of American consumers as a whole. Among low- and middle-income Americans who carried credit card debt, our study finds that total average credit card debt fell 28 percent—from $9,887 in our 2008 survey to $7,145 in 2012. Among Latino households, the average credit card debt was lower but the decline was comparable: credit card debt fell 30 percent from $8,661 in 2008 to $6,066 in 2012. The number of credit cards that indebted households possessed also declined: in 2008, Latinos with credit card debt reported having 4.14 cards on average. In 2012, the average number of credit cards fell to 3.73.

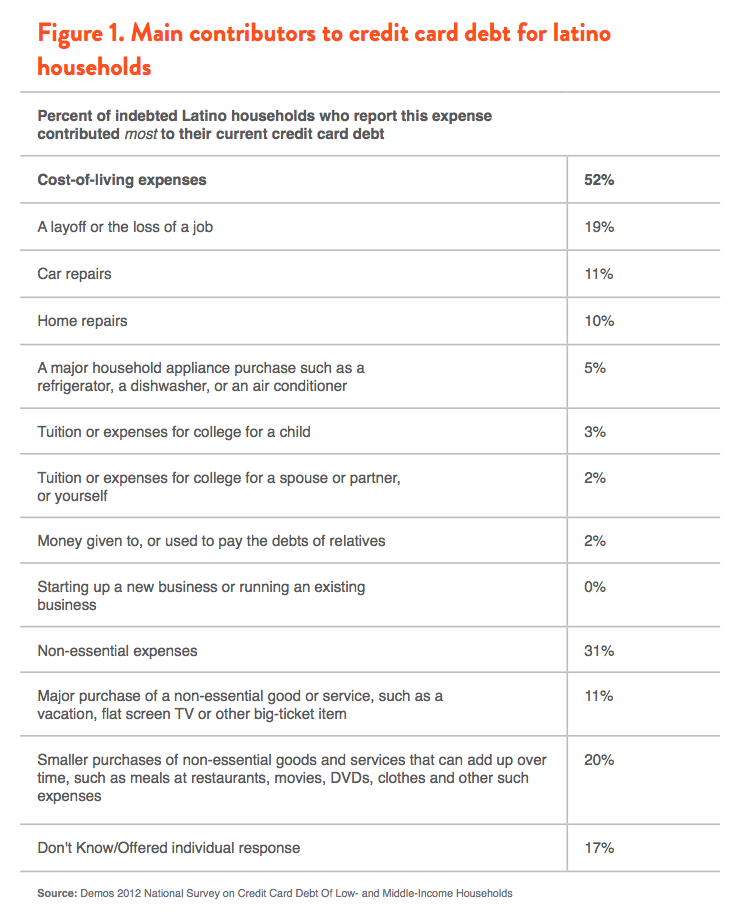

While it’s a positive sign that households are paying down debt overall, patterns of credit card usage still raise serious concerns. More than 4 in 10 Latino households with credit card debt report that they relied on credit cards to pay for basic living expenses when paychecks and savings were not enough to make ends meet. Forty-three percent of indebted Latino households report using their credit cards for basic living expenses like rent, mortgage payments, groceries, utilities, or insurance because they did not have enough money in their checking or savings accounts, a rate that is similar to the survey population as a whole. And while some indebted Latino households also used credit cards for entertainment, vacations, and other “extras,” these were not the main drivers of credit card debt. When asked about the single expense that contributed most to credit card debt, only a third of Latinos cited non-essential costs, big or small. Instead, as we will explore more deeply in this paper, medical expenses and costs associated with unemployment were major contributors to debt for low- and middle-income Latino households.

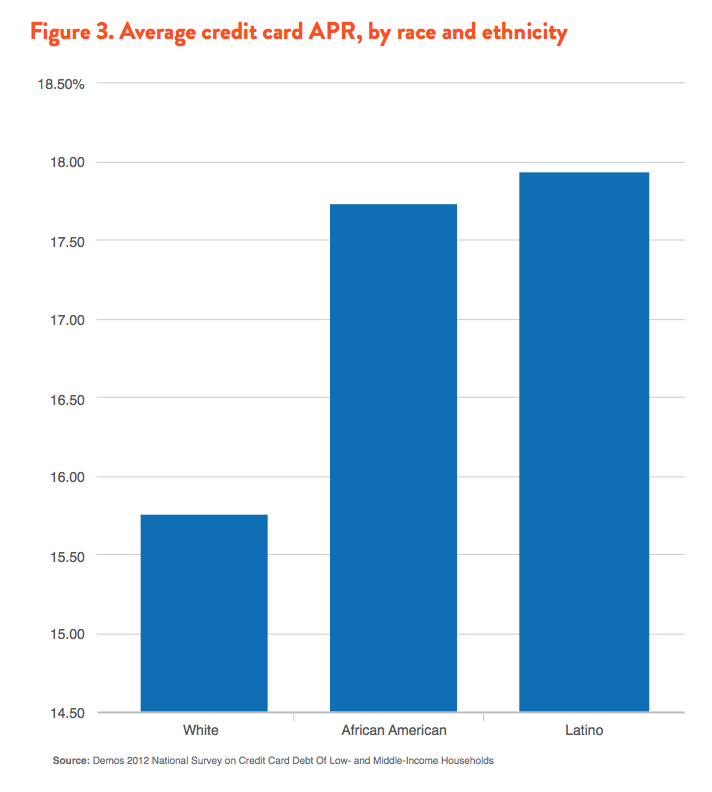

Whatever the source of credit card debt, it comes at a steep cost as interest charges accumulate. On average, Latinos report annual percentage rates (APRs) of 17.93 percent on the card where they carry the highest balance, a significantly higher rate than the 16.13 percent average for indebted households overall. The high interest rate paid by the average Latino borrower means that they will ultimately pay more in interest over the duration of their debt even though they carry lower average balances. For example, a Latino family carrying the average credit card debt load of $6,066 and average APR, making the average monthly payment, would be charged at least $300 more in interest than the average white family, even though they borrowed less. To make matters worse, 29 percent of Latino borrowers report extremely high APRs, with interest rates topping 20 percent or more.

Imperfect credit may be one reason for the higher average interest rates paid by Latino credit cardholders. Many experts suggest a credit score of 700 or higher is needed to qualify for loans (including credit cards) with a lower rate of interest. Among indebted households that report knowing their credit score, just 40 percent of Latinos report a credit score above 700 compared to 59 percent of white households. At the same time, 68 percent of indebted Latinos report that they do not know their credit score, compared to 59 percent of the indebted population as a whole. Yet becoming more familiar with the credit scoring system may only go so far in helping Latino cardholders to improve their credit standing. Indeed, as the following sections will demonstrate, factors like unemployment and lack of health insurance are among the main drivers of credit card debt for Latinos. These larger social forces, which disproportionately impact the Latino community, cannot be addressed simply by increasing awareness of credit scores or how credit operates.

Medical costs and credit card debt

The growing cost of health care strains the budgets of many American households, as families struggle to keep up with rising premiums, deductibles, and co-payments, or to find affordable care if they are uninsured.9 Medical expenses are frequently unplanned and unavoidable, forcing households that lack substantial savings to take on debt to meet the costs. Dealing with health costs is a particularly serious challenge for Latinos because they are less likely to have health insurance coverage, increasing the odds that health costs become a significant source of debt.

The U.S. Census Bureau finds that 29 percent of Latinos were uninsured in 2012—a rate nearly twice that of the population as a whole.10 In our sample of low- and middle-income Latino households carrying credit card debt, 43 percent report that in the past year they or someone in their household has been without medical insurance and 38 percent report that they or someone in their household is currently without health insurance—both significantly higher rates than the population as a whole. Yet there is reason for hope: as the federal Affordable Care Act goes into effect, insurance coverage by both Medicaid and private plans is expected to increase. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that as many as 10.2 million uninsured Latinos have new opportunities for affordable health insurance coverage as a result of the Affordable Care Act.11 By 2013, the proportion of Latinos without health coverage had already fallen six percentage points, according to the Census Bureau, likely as a result of the early effects of the law.12

Despite these potential improvements on the horizon, medical debt will likely continue to burden the Latino community into the foreseeable future. A number of barriers—including immigration status, difficulty documenting income, the low proportion of Latinos who receive health coverage from their employers, and the reluctance of several states to expand Medicaid coverage—still stand in the way of full insurance coverage for the Latino population. And even when households do secure coverage, costs such as insurance deductibles, co-payments, and prescriptions may still be difficult to afford. At the same time, medical debts that accrued before families had coverage will continue to accumulate interest until they are paid off in full.

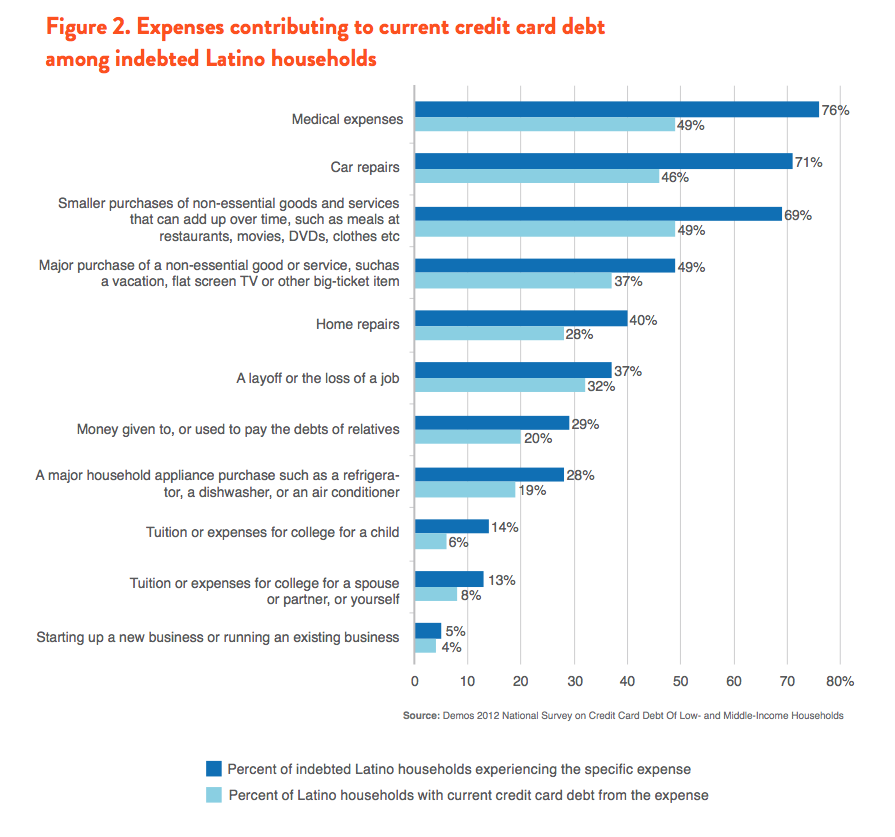

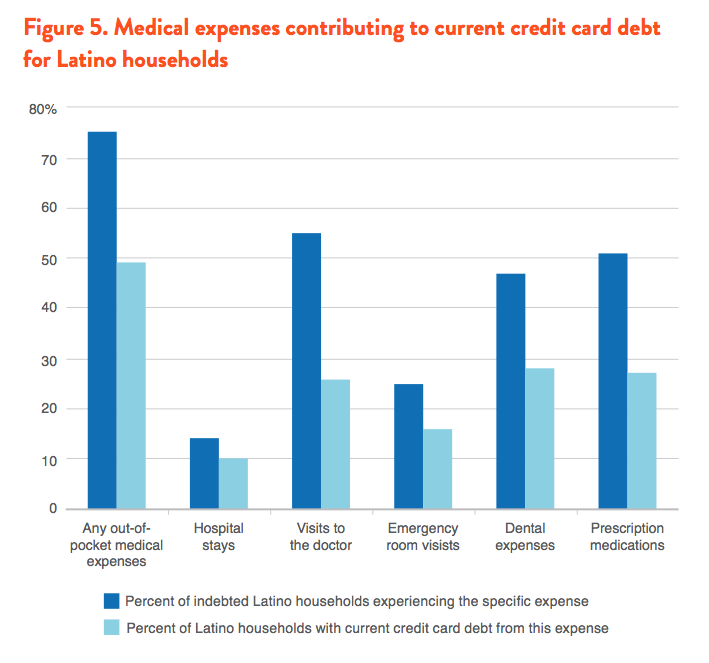

The reality is that everyone eventually has health care needs and incurs out-of-pocket expenses. Three-quarters of low- and middle-income Latinos carrying credit card debt report that their household incurred some out-of-pocket medical expense in the last three years, a rate comparable to the rest of the indebted population. However, Latino households were significantly more likely than others to amass additional credit card debt as a result of these medical costs. For example, 73 percent of indebted Latinos who experienced hospital stays report that the associated expenses contributed to their credit card debt, compared to 56 percent in the indebted population who experienced hospital stays as a whole.13 At the same time, 53 percent of indebted Latinos who incurred out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs reported that these expenses contributed to their credit card debt, compared to just 46 percent of the indebted population as a whole who paid for prescription drugs. The higher debt levels are a plausible result of Latinos’ lower rates of insurance coverage, since out-of-pocket costs tend to be higher for the uninsured.14

In total, Latinos with medical debt on their credit cards report it amounts to an average of $1,521 or 25 percent of their average total credit card debt. In addition, approximately a third of indebted Latino households also have medical debt that is not on their credit cards—an average of $3,648, down significantly from $5,430 in 2008. This debt may be in the form of outstanding medical bills, medical bills that are being paid over time according to a payment plan, or payday loans or other types of personal borrowing used to pay for medical expenses.

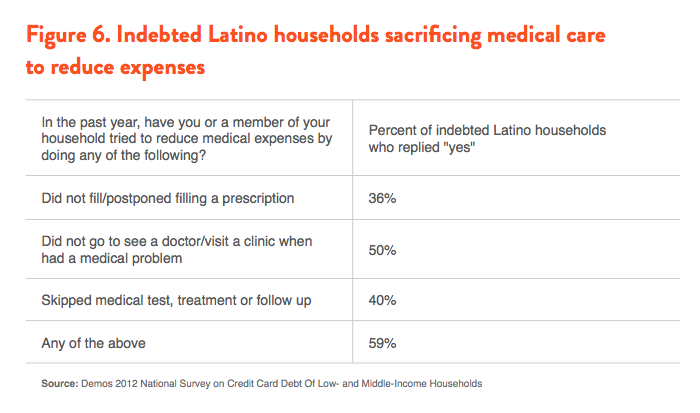

High medical costs—and the concern that they could lead to greater debt—deterred many indebted Latino households from pursuing recommended medical care, often in ways that could negatively affect their health. Most troublingly, half of indebted Latinos report that they did not visit a doctor or clinic when they had a medical problem in order to reduce medical expenses. This is significantly more than the 39 percent of indebted households overall who report this cost-cutting behavior. At the same time, 40 percent of Latinos report they skipped a medical test, treatment, or follow-up to reduce their medical expenses, while 36 percent of Latino households report that they did not fill a prescription or postponed filling a prescription to reduce medical expenses. Policies such as those enacted via the Affordable Care Act promise not only to cut health care costs and reduce medical debt, but can also decrease the incentives that lead households to sacrifice medical care in an effort to save money. In the meantime, credit cards can provide the immediate funds a family needs when faced with an emergency, but at the cost of additional debt and interest payments.

Discriminatory treatment and fraud targeting

Latino cardholders

In addition to the broad opportunities and challenges of credit access and credit card debt, the Latino community also faces a disproportionate share of credit card scams and episodes of discriminatory treatment. In a wide-ranging recent report on consumer fraud in the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) found that Latinos were more likely than whites to have been victims of consumer fraud, particularly debt-related scams such as false promises to reduce credit card debt, provide credit card “insurance,” or reduce interest rates for a substantial fee.15 The FTC found numerous cases of credit card-related fraud victimizing Latino consumers in both English and Spanish, but suggested that consumers who try to handle complex financial transactions in English when they do not have full command of the language might be particularly susceptible to fraud.

Language was also an issue in the federal government’s largest credit card discrimination settlement in history, a resolution reached with GE Capital Retail Bank in June 2014. In this case, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that the bank excluded 108,000 credit cardholders from promotional programs it offered to help consumers with low credit scores and high credit card balances to reduce their credit card debt. According to the settlement, GE Bank “did not extend these offers to any customer who indicated that they preferred to communicate in Spanish or had a mailing address in Puerto Rico, even if the customer met the promotion’s qualifications. This meant that Hispanic populations were unfairly denied the opportunity to benefit from these promotions… [these] the customers did not receive either offer in any language, including English, and did not know they were being discriminated against.”16 Ultimately, the company agreed to pay $169 million to the cardholders in compensation and to pay additional fines for its misconduct.

“Consumers deserve to be treated fairly no matter where they live or what language they speak,” announced Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Director Richard Cordray. Unfortunately, the continued prevalence of credit card fraud and discrimination targeting the Latino community indicates that fair treatment is not yet a reality.

Unemployment and credit card debt

With 2.4 million Latinos out of work in 2012 and another 2.5 million either under-employed or marginally attached to the labor force, it is not surprising that expenses associated with job loss were cited as one of the greatest contributors to Latino households’ credit card debt over the past three years. The unemployment rate for Latinos was 10.3 percent in 2012, compared to 8.1 percent for all households.17 Nearly one in four indebted Latinos report that in the last three years they or a member of their family has lost a job or been unemployed for at least 2 months. Among the households experiencing unemployment, 87 percent report it has contributed to their current level of credit card debt. Overall, nearly 1 in 5 Latinos with credit card debt say that a layoff or other loss of a job is the expense that contributed most to their current level of credit card debt. This proportion is not statistically different from the 15 percent of indebted households overall reporting that job loss was the main contributor to their current credit card debt.

Paying down debt and saving: optimism and challenges

Digging out of debt can be a slow process for anyone, but Latinos are more optimistic about paying down their credit card debt swiftly than indebted Americans as a whole—53 percent predict they will be completely out of credit card debt in just six months, compared to 43 percent of indebted households overall. This is a reversal from our survey findings in 2008, when Latinos were less likely than others to think they would be completely out of credit card debt in six months.

However, there are reasons to be cautious about the prospects for paying off credit card debt: while Latino households’ average credit card balance is lower than the average of other indebted households, Latinos also report that they pay less per month—an average $483 on their credit cards in the past month, compared to $566 for all indebted households. At the same time, Latinos pay higher average interest rates on their debt, meaning higher payments would be needed to clear their average credit card debt in a six month period. Finally, 36 percent of indebted Latino households report that they “always” or “usually” make only the minimum payment due each month on all of their credit cards. Paying only the minimum allows interest charges to accrue more quickly, making it more difficult to emerge from debt.

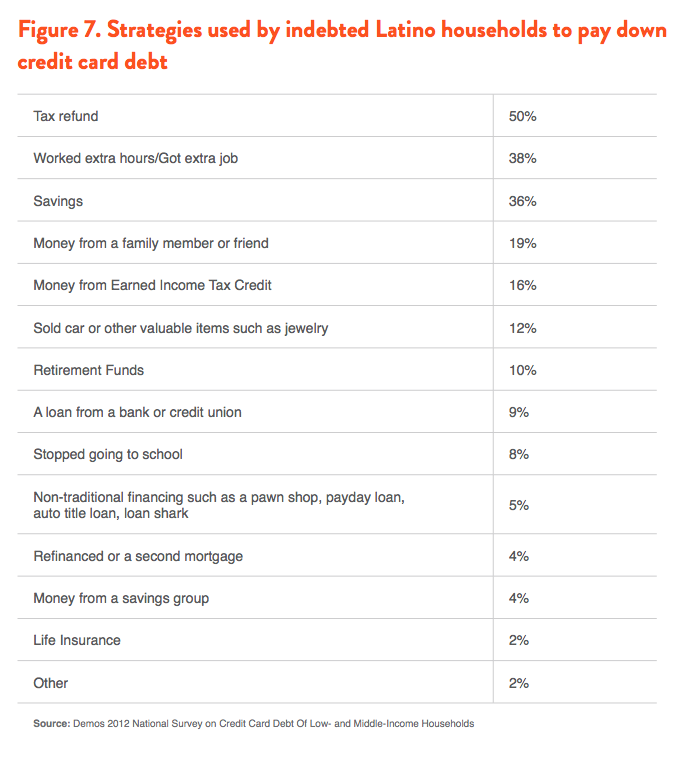

Nevertheless, indebted Latino households report several solid strategies for paying down their credit card debt. Half of Latino households say they use tax refunds to pay down debt, while 38 percent report that they paid down debt by working extra hours or getting an additional job. Other popular strategies included drawing on savings (36 percent) and borrowing or receiving gifts of money from family or friends (19 percent). These common means of paying down credit card debt were not significantly different from responses of the indebted population as a whole.

In addition to paying down debt, building up savings helps households to stabilize their financial situations. Savings can provide vital resources to meet special expenses or emergency costs without having to go further into debt. The ability to save on a monthly basis is thus a key sign of financial health. In our sample of low- and middle-income Latino households with credit card debt, 60 percent of households responded that they were not currently saving money each month. The reason for not saving was overwhelmingly the same—79 percent of Latino households said “there is no money left over after paying all the bills.” There is also a widespread perception that saving money is becoming more difficult: 68 percent of Latino households report that it’s harder than it was three years ago to save, and 62 percent assert that it is harder to save than it was just one year ago. Yet Latino households’ monthly struggle to keep up with bills in the present is tempered by optimism about a brighter future where credit card debt will be paid down quickly.

The Credit CARD Act provides new protections to Latino borrowers

In May 2009, President Obama signed the Credit CARD Act into law, requiring credit card companies to comply with new standards of fairness and transparency for billing and fees. The CARD Act mandates that monthly credit card statements include new disclosures, detailing how long it will take to pay off the entire credit card balance if a consumer only pays the minimum amount due as well as information about interest and fees. In addition, the CARD Act eliminated some harmful practices such as card issuers’ ability to retroactively apply a higher interest rate to an existing credit card balance. Under the Act, companies must also provide adequate time for a consumer to receive and pay their bill before a late fee is imposed. While the benefits of the CARD Act have been felt by consumers broadly, Latino consumers have especially benefitted, reporting that they are now paying down debt more quickly and saving money by avoiding unfair fees.

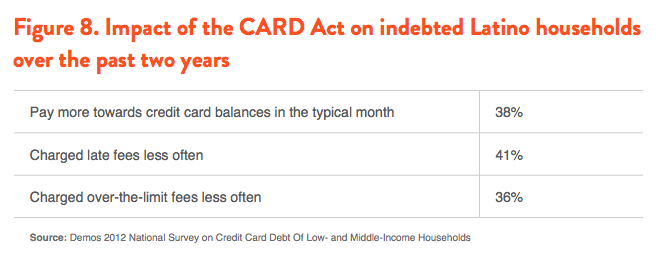

Ninety percent of indebted Latino households report that they noticed a change in their monthly credit card statements since the passage of the CARD Act, and many report that the new information has changed their behavior. In total, 38 percent of Latino households say the new disclosures about how long it will take to pay down their credit card debt has caused them to pay more toward their credit card balance in the typical month.

Overall, credit cardholders report that they are being charged late fees less frequently as a result of the CARD Act, and this is even truer of Latino households. As a result of the longer billing cycles mandated by the CARD Act, 41 percent of indebted Latino households report fewer late fees, compared to 26 percent of indebted households overall. The benefits are more clear when it comes to over-the-limit fees—one of the most abusive credit card practices documented before the passage of the CARD Act. These fees were charged whenever consumers spent more than their credit limit. The fees were regularly imposed without notifying consumers when they made the over-the-limit transaction, regardless of whether consumers would have preferred that transactions above the limit simply be denied. The CARD Act required consumer authorization for going over the credit limit, virtually eliminating over-the-limit fees. Overall, 22 percent of indebted households report that they have benefitted from the elimination of over-the-limit fees. Latinos have benefitted even more, with 36 percent reporting that they are now charged over-the-limit fees less often.

For Latino consumers in particular, the CARD Act has made credit cards a safer financial product, helping households to reduce their fees and pay down their balances more quickly.

Policy Recommendations

The financial crisis damaged household stability, but our survey shows that the trends pushing households into debt started long before the recession and they continue as the economy returns to normal rates of growth. The loss of vital public services and support for the programs that allow low- and middle-income families to prosper—like low cost educational opportunities, affordable health care services, and labor policies that provide a decent standard of living—made it increasingly difficult for families to get by without taking on debt.

Americans should not have to rely on credit cards to supplement low pay and replace social support. Policies that give households the ability to survive without depending on debt are the primary means to put families back on stable ground. Our survey shows that 87 percent of indebted Latino households affected by unemployment expenses in the past year had to take on credit card debt as a result. As the economy continues a slow crawl toward previous employment levels, reducing barriers that keep laid-off workers from qualifying for unemployment insurance and extending eligibility for unemployment insurance to include more low-wage and part-time workers when they’re laid off can prevent hardship. At the same time, those who have jobs would benefit from the kind of workplace protections that promote living wages, affordable health and retirement benefits, and secure employment. Policies that ensure that all American jobs meet basic standards of decent employment would give low- and middle-income households the boost they need to make ends meet without reliance on credit. Raising the minimum wage, protecting the right to collective bargaining, and enforcing current labor standards all contribute more effectively to the ability of households to support themselves without taking on credit card debt.

In addition to shared investments that put our country on the right track for workers and their families, our survey points to three areas where policy can make a difference in household budgets: medical debt, financial regulation, and credit reporting.

Medical Debt Protection Emergency health expenses can run into the thousands of dollars and burden families for years after they have recovered from the physical trauma. In the decades since the 1970s, employers shed health care benefits as a provision of employment and households turned to debt to finance critical health expenditures. After decades without a policy response, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) finally offers a solution that can lower the individual cost burden for health care. Yet medical debt will not cease to exist, and the rising cost of health services and lower insurance rates among people of color make it difficult to guarantee adequate coverage and quality of care. Since medical debts continue to accrue, there must be fair and non-discriminatory practices for their collection. Medical lending practices should not be permitted to use evaluations of the total credit available to patients. The appropriate financial services guidelines for health care facilities should be under the purview of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Moreover, as unexpected medical expenses offer little information about the character of the consumer, medical debt should excluded from credit scores altogether.

Borrower Security Many moderate-income Latino households rely on credit to make investments in their futures, and often just to meet their basic needs. Because credit plays an essential role in the financial security of Americans, it should be governed by fair and responsible practices. The CARD Act began the industry reforms necessary to establish prudent guidelines and accountability for credit card companies. Federal legislation protecting borrowers by setting national usury limits, indexed to a federal rate, would complement the provisions of the CARD Act. Such legislation would provide borrower security by eliminating unjustifiably high interest rates on credit products ranging from credit cards to student loans and limiting late fees to $15 per late payment. Several states have already enacted reforms that cap the interest rates of high-cost payday loans, showing the possibilities for state and local legislation to regulate the industry and protect consumers.

Fairness in Bankruptcy Indebted Latino households need reasonable and straightforward options as they work toward restoring their balance sheets. As a last resort, declaring bankruptcy should provide the opportunity for families to reconcile their debts, including mortgage and student debt. In order to make bankruptcy a fair option to consumers, bankruptcy law should permit courts to restructure the debt on home mortgages by setting interest rates and principal at commercially reasonable market rates and extending repayment periods, allow judges to reduce the mortgage principal on a primary residence to the current value of the home, and to discharge student loan debt. Incorporating student loans into bankruptcy policy will make it possible for families to work for a better future without being crippled by the cost of education.

Fair and Accurate Credit Scores Our survey found that Latino households are less likely than whites to report a good or excellent credit score, aligning with a larger body of research showing that credit scores correlate with race and ethnicity. The CFPB could play a stronger role in this area, beginning with improvements in the transparency, validity, and appropriate use of credit reports and scores to ensure accuracy and accessibility of credit reports and the regulation of reporting information. In addition, all medical debt, disputed claims, and unsafe credit products should be excluded from credit reports, steps the CFPB is already taking in the case of medical debt. The improvement of reporting and access would reduce the biases in credit scores and improve the economic security of both borrowers and lenders.

Ban Employment Credit Checks Today, employers commonly look into the credit histories of job candidates as part of the hiring decision. While there is no evidence linking credit reports to trustworthiness or dependability, credit reports have repeatedly been shown to have race and income biases that make the practice of employment credit checks highly discriminatory.18 Using credit reports as criteria for hiring exacerbates the economic hardships facing households that may have had a medical emergency, a divorce, a layoff, or other economic impacts beyond their control. Ten states have already passed legislation limiting the use of employment credit checks because of these issues. We suggest that the US adopt the Equal Employment for All Act, a federal law establishing uniform restrictions on credit checks for employment.

Regulating Non-traditional Lenders The exorbitant interest rates that accompany payday loans—with rates as high as 400 percent annually—can trap consumers in a spiral where low income requires increasingly high borrowing, even for small loans.19 Although more than 12 million Americans turn to this source of credit each year, the industry preys on borrowers in the weakest financial positions who use the loans for basic living expenses like rent, utilities, food, and emergency repairs.20 Federal legislation could be modeled on strong usury laws at the state-level that prohibit payday lending entirely, or restrict it with double-digit caps on the allowable interest rate. To date, 17 states and Washington, DC, have enacted legislation capping the allowable interest rate on payday loans. Other laws limit the maximum amount and length of borrowing in the industry; according to the Center for Responsible Lending, one such law has already saved consumers more than $122 million in fees.21 In addition to direct regulation of non-traditional lenders, the federal government should encourage affordable alternatives for the populations most likely to rely on last-minute emergency loans.

Extend the Successes of the CARD Act The CARD Act is working for American households by standardizing best practices industry-wide. Our research and recent data from the CFPB show that consumers are better equipped to make informed choices and less subject to abuses in the areas addressed by the legislation—such as fair and transparent pricing.22 The provisions of the CARD Act include protections that grant consumers better knowledge and control over their finances, including requiring credit card providers to make the due dates for payment the same each month, allocating payments made above the monthly minimum to the highest interest rate balance first, and eliminating high-fee over-the-limit spending unless customers explicitly opt-in to the service. American households have seized this opportunity to pay down balances and avoid fees.

Some card issuers responded to the legislation with voluntary product improvements, including an increased commitment to customer service and attention to received complaints.23 Yet problems of inadequate transparency and injurious costs remain. In their evaluation of the CARD Act, the CFPB identified a number of areas where credit card companies could promote higher standards of service. The best practices would treat add-on products, such as supplementary protections and credit monitoring, with the same standards of transparency and disclosure as are required for lines of credit, even when provided through third-party contracts. Application fees—currently excluded from the standard imposed by the CARD Act that states that fees cannot exceed 25 percent of the total credit line in the first year—would be included in the first-year calculation of fees to ensure that the ratio of costs to credit remains reasonable. Moreover, a high standard for clear disclosure related to rewards programs, grace periods, and products that defer interest for an introductory period, would complement the practices already covered by the CARD Act.

Endnotes

- According to the Business Cycle Dating Committee, National Bureau of Economic Research, the Great Recession officially ended in June 2009.

- In addition, Latino communities are particularly concentrated in states such as Arizona, California, Florida and Nevada where the housing bubble was most inflated and the crash was greatest, compounding the loss of Latino wealth.

- Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, “The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap,” Institute on Assets and Social Policy, Brandeis University, February 2013. http://iasp.brandeis.edu/pdfs/Author/shapiro-thomas-m/racialwealthgapbrief.pdf

- Shapiro, Meschede, and Osoro, “Racial Wealth Gap.”

- Demos analysis of the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finance

- See for example: Janis Bowdler, “Survival Spending: The Role of Credit Cards in Hispanic Households,” National Council of La Raza, January 2010. http://www.nclr.org/images/uploads/publications/file_Survival_Spending_Final_Jan_19_10docx_1.pdf

- Demos analysis of the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finance

- Overall population estimates from the 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

- “Health Care Costs: A Primer,” Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012. http://kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/health-care-costs-a-primer/

- U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplements, 2013.

- “The Affordable Care Act and Latinos,” US Department of Health and Human Services, accessed October 6 2014. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/factsheets/2012/04/aca-and-latinos04102012a.html

- Jessica C. Smith and Carla Medalia, “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2013,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 2014. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-250.pdf

- Figure 5 illustrates that 10 percent of the indebted Latino population has debt from hospital stays—this number differs from the 73 percent cited because it includes both Latinos who experienced hospital stays in the last three years and those that did not.

- See for example: Gerard F. Anderson, “From ‘Soak The Rich’ To ‘Soak The Poor’: Recent Trends In Hospital Pricing,” Health Affairs vol. 26 no. 3 (May 2007) 780-789. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/26/3/780.full?sid=722f52f2-139d-4a61-af4f-b922517b7416

- “Consumer Fraud in the United States, 2011,” Federal Trade Commission, April 2013. http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/consumer-fraud-united-states-2011-third-ftc-survey/130419fraudsurvey_0.pdf

- “CFPB Orders GE Capital to Pay $225 Million in Consumer Relief for Deceptive and Discriminitory Credit Card Practices,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, June 19, 2014.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, 2012.

- Amy Traub, “Discredited: How Employment Credit Checks Keep Qualified Workers out of a Job,” Demos, 2013. http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Discredited-Demos.pdf

- Center for Responsible Lending, “How a Short-term Loan becomes a Long-term Debt,” http://www.responsiblelending.org/payday-lending/.

- Pew Charitable Trusts, “Payday Lending in America: Who Borrows, Where they Borrow, and Why,” http://www.pewstates.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2012/Pew_Payday_Lending_Exec_Summary.pdf.

- Center for Responsible Lending, “How a Short-term Loan becomes a Long-term Debt,” http://www.responsiblelending.org/payday-lending/.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “CARD Act Report: A Review of the Impact of the CARD Act on the Consumer Credit Card Market,” October 1, 2013, http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201309_cfpb_card-act-report.pdf.

- Ibid, 7.