In today’s economy, a college education is essential for getting a good job and entering the middle class. Yet, despite this reality, college costs are rising beyond the reach of many Connecticutters. State policy decisions have played a significant role in this rise by shifting costs onto students and families through declining state support. Connecticut’s investment in higher education has decreased considerably over the past two decades, and its financial aid programs, though still some of the country’s most expansive, fail to reach many students with financial need. Students and their families now pay—or borrow—much more than they can afford to get a higher education, a trend which will have grave consequences for Connecticut’s future economy.

The Great Cost Shift: How Higher Education Cuts Undermine The Future Middle Class.

This brief is based on the Demos report “The Great Cost Shift,” which examines how nationwide disinvestment in public higher education over the past two decades has shifted costs to students and their families. The report outlines how such disinvestment is magnified by rapidly rising enrollments, and its effects are felt particularly acutely as student bodies become more economically, racially, and ethnically diverse. This fact sheet focuses on Connecticut, highlighting the trends in the state’s higher education funding over the last twenty years.

State Higher Education Funding Is Dramatically Declining

Connecticut’s overall funding for higher education has declined precipitously since its pre-Great Recession peak in 2008. Funding per student in the state, although still above the national average, has fallen even more dramatically, since enrollments have risen significantly even as total funding fell. Though state funding for higher education has historically risen and fallen in tune with the business cycle, the post-Great Recession decline appears to be a worrisome departure from the historical pattern.

- Overall, Connecticut’s higher education funding fell from its peak of $1.14 billion in 2008 to $957 million in 2013, a 14 percent decline.

- Funding per full-time equivalent (FTE) student has fallen 22 percent since 2008, and 28 percent since 2000.

- Despite this decline, Connecticut’s funding per FTE student—$10,655 in 2013—still ranks 5th in the nation, well above the national average.

Skyrocketing Tuitions

Connecticut’s declining state financial support for its public colleges and universities has translated into higher tuition and fees, making college increasingly unaffordable for the state’s students.

- Over the past two decades, average yearly tuition and fees at public 4-year institutions in Connecticut have risen by $5,453, a 134 percent increase.

- Tuition and fees have risen more slowly at 2-year institutions, climbing 111 percent, or $1,888, over the same period.

- Tuition prices at both 4- and 2-year institutions in Connecticut have been consistently higher than the national average for the past two decades, a gap which has stayed relatively level over the period.

Grant Aid Has Become Much Less Generous

Exacerbating the decline in overall higher education appropriations, funding for Connecticut’s main grant financial aid programs have plummeted since the Great Recession. The average grant has fallen even more precipitously, decreasing its buying power for the 59% of Connecticut students who receive the grants.

- Total Connecticut grant aid has fallen by 36% since 2008.

- The average award has fallen to just $1,780 in 2013, a decline of 29% from its 2008 level.

- Because average grants have fallen as tuition has risen, the grants are paying for a sharply declining share of tuition costs: the average grant covered just 19 percent of average tuition at a 4-year school in Connecticut in 2013, down from 46 percent in 2001.

- The State Grant program benefits approximately 28% of all students.

Shifting Costs To Students And Families

Tuitions have been rising far more rapidly than family incomes, causing the tuition costs to take an increasingly large bite out of family budgets. The increasing unaffordability of a college education in the state combined with the decreasing share of tuition covered by Commonwealth grants have forced Connecticut’s students to borrow more to pay for school.

- In 2000, average tuition and fees alone at the average public 4-year institution in Connecticut cost 8 percent of a median household’s income; by 2012 this share had reached 13 percent.

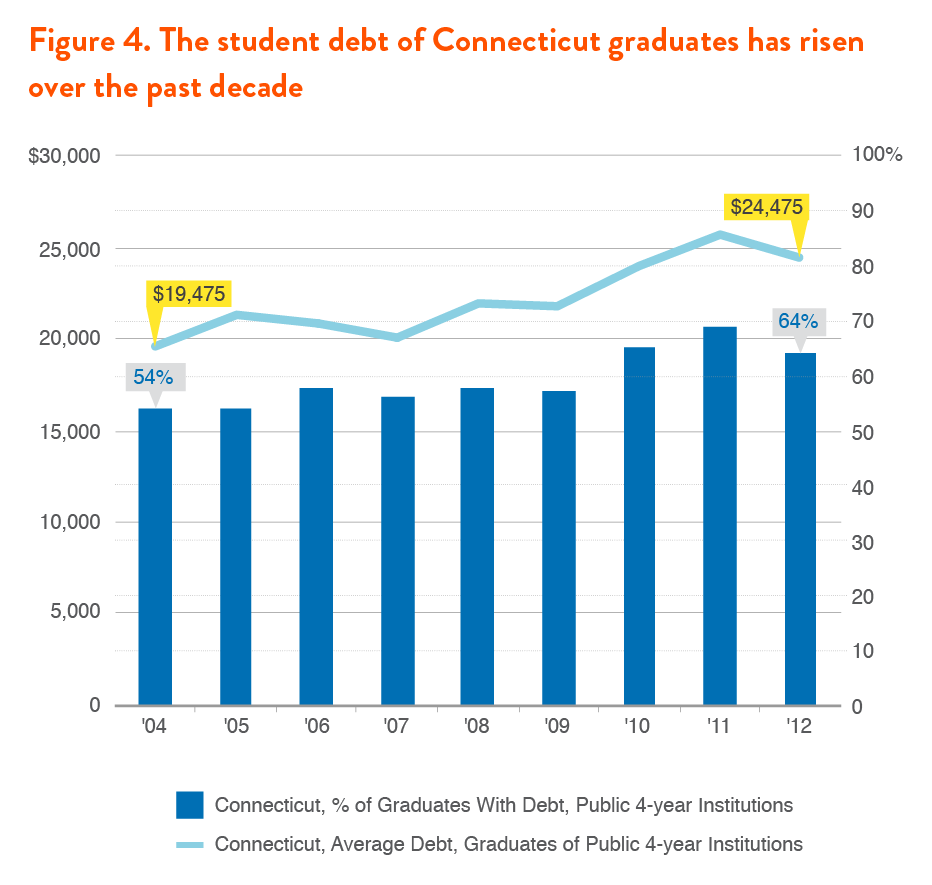

- Sixty-four percent of students graduating from public 4-year colleges in Connecticut in 2012 left with some student debt, much higher than the 54 percent who left indebted in 2004.

- The average debt of indebted graduates has risen precipitously. Indebted students graduated with an average of $24,475 in debt in 2012, a 26% rise since 2004.

- Even after accounting for federal, state, and institutional grant aid, Connecticut’s students pay an average of $11,870 (including room and board) to attend public 4-year institutions, an increase of 10% since 2008-09, a few hundred dollars more than the national average. Low-income students (those from families making less than $30,000 annually) have seen their costs rise dramatically; they now pay an average of $9,552 after all grant and scholarship aid, an increase of 22 percent in just 4 years. In fact, low-income students in Connecticut pay higher-than-average net prices at public schools, a reversal from four years ago, when net costs for low-income students were slightly below the national average.

- Connecticut’s 2-year students, however, fare somewhat better. After accounting for grant aid, the state’s students pay an average of $5,788 to attend 2-year schools, more than $1,400 less than the national average. Low-income students at 2-year schools in the state fare better as well, paying an average of nearly $1,000 less than 2-year students nationwide.

Increasing Enrollments, High Enrollment And Completion Rates

Despite the increasing cost of a higher education, enrollments at Connecticut’s colleges and universities have risen steadily over the past two decades, in part due to the high share of Connecticut’s high school graduates that enroll in college. Graduation rates at the state’s 4-year schools, too, continue to outpace those of the country as a whole. However, one blot on Connecticut’s higher education outcomes is its graduation rate from 2-year institutions, which is well below the national average.

- Total FTE enrollments at Connecticut’s colleges and universities have risen steadily, increasing 27 percent from 70,870 FTE students in 1991 to 89,842 in 2013.

- Enrollments as a share of the young adult population have also risen, from 20 percent of all young adults enrolled in higher education in 1991 to 27 percent in 2013.

- Connecticut has a very high enrollment rate: 78.7 percent of Connecticut’s high school graduates enrolled in higher education in 2010. This is the 2nd-highest share of any state in the country, well above the national average of 63 percent.

- The graduation rates at Connecticut’s 4-year colleges and universities also outpace the nation. As of 2010, 61.5% of students at the state’s public 4-year institutions graduated within 6 years, a rate 5 percentage points above the national average and the 12th highest in the nation.

- However, the share of students at the state’s 2-year institutions who graduated within 3 years was just 10.5% in 2010, nearly 10 percentage points below the national average and the 4th lowest in the country.

What Needs To Happen?

Even though Connecticut’s graduation rates from its 4-year public colleges and universities are well above the national average, they are still too low to meet the future demands of the state’s labor market, which will increasingly require a postsecondary credential. Sixty-five percent of all jobs in the Constitution State are projected to require some sort of postsecondary education by 2018, yet just 47 percent of young Connecticutters (ages 25-34) currently have an associate’s degree or higher. This share is not projected to improve much in the near future: by 2018, just 49 percent of all working-age Connecticutters are projected to hold a two-year degree or higher, leaving the state with a significant educational gap in its labor market. Fortunately, Connecticut can still close this projected gap by taking advantage of our state’s resources to invest in the current and future generations of Connecticutters aspiring to realize the American Dream through postsecondary education.

With recent cuts in state need-based aid, and the ensuing rise in costs for low-income students, Connecticut is endangering the mission of upward mobility inherent in the public higher education system. By increasing need-based aid, Connecticut would be able to offer the promise of affordable higher education to the very groups that are underrepresented in our higher education system—groups that stand to benefit the most from higher education. Even beyond these students, Connecticut is endangering the quality of its institutions of higher learning by spending less per student than a generation ago, threatening the state’s economic competitiveness and the future of its young people. To reverse course, the state will need to commit to bold solutions that can strengthen and stabilize funding for Connecticut’s state universities and colleges, and provide greater financial support to deserving students.