McCutcheon Money: How Citizens United Two Could Increase the Power of Elite Donors

$123,200 is the current “aggregate contribution limit” — AKA, the total amount of money one wealthy individual is permitted to contribute to all federal candidates, parties, and PACs. The Supreme Court will consider this cap in McCutcheon.

Next Tuesday, October 8 the Supreme Court is scheduled (pending shut-down nonsense) to hear oral argument on McCutcheon v. FEC, a challenge to the total cap on the amount of money one wealthy individual is permitted to contribute to all federal candidates, parties, and PACs.

The current “aggregate contribution limit” is $123,200—twice the median household income in the U.S. As you might imagine, this cap affects very few people; just 1,219 people were at, over, or within 10% of the limit for the 2012 election cycle.

I’m guessing you are not sitting on $150,000 you’d like put into politics next year—so, why should you care?

Here’s why: this tiny group of people already has substantial sway in our election system, and a bad ruling in McCutcheon would give them even more.

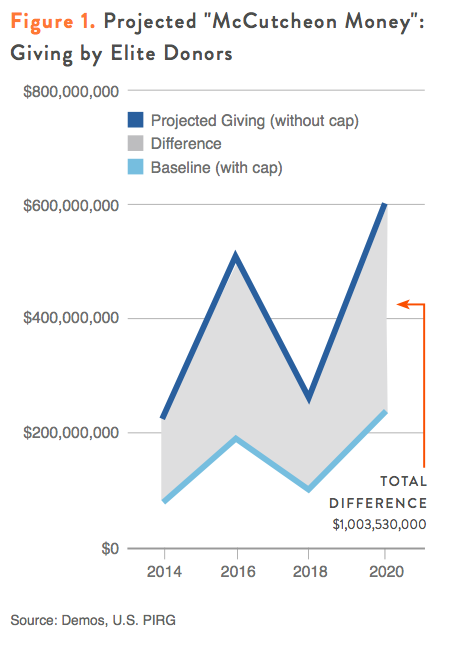

Demos and U.S. PIRG have worked together to project that striking aggregate contribution limits would bring more than $1 billion in additional campaign contributions from elite donors through the 2020 elections.

This figure does not represent a sea change when compared to existing spending levels, but it would boost the power of this tiny segment of elite donors, especially compared with small contributors.

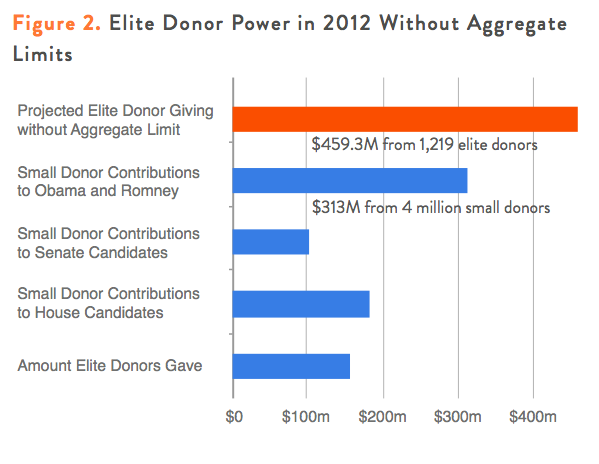

For example, we estimate that without aggregate limits, in 2012 the 1,219 elite donors mentioned above would have given nearly 50% more money to candidates, parties and PACs than President Obama and Governor Romney raised together from more than 4 million small donors.

Under current case law, the Supreme Court should uphold aggregate contribution limits as a decades-old protection against corruption, the appearance of corruption, and circumvention of base contribution limits. But, the Roberts Court has been willing to toss precedent aside to gut campaign finance laws in the past—so it’s important to understand the real-world consequences of the Court striking a federal contribution limit for the first time ever.

A bad ruling would bring even more rule by the money instead of the many.

In addition to shifting the power dynamic between the very wealthy and ordinary citizens, striking limits would increase elite donors’ influence over elected officials by making officeholders increasingly dependent upon this small slice of the population for campaign funds. The undue and increasing power of large donors fuels the public’s mistrust of government and the widespread appearance of corruption that aggregate limits are intended to combat.

Demos detailed how government’s responsiveness to large donors fuels the appearance of corruption in an amicus brief to the Supreme Court signed by U.S. PIRG and other organizations representing 9.4 million members and supporters. To view a plain-language version of the brief with charts and graphs, click here.

Trust in Congress was already at an all-time low before the current government shut-down. The Supreme Court should stick to precedent and uphold reasonable contribution limits—not give the public even more reason to throw up their hands at the craziness in Washington.