Absolute and Relative Mobility, A Short Primer

“Relative mobility” measures how a child’s ranking in the income distribution compares to her parents'. “Absolute mobility” measures something entirely different.

The economics blogosphere as well as mainstream publications are alight with new research from Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez and Nicholas Turner on upward mobility. It’s a key topic, especially here at Demos, where we want an equal chance for all. I haven’t finished reading the paper and related commentary, which I plan to do over the weekend, so I don’t want to comment on it, other than to note a very important distinction between absolute mobility and relative mobility that may get lost in the fray.

Chetty, et. al., are looking at what is called “relative mobility.” Relative mobility measures how a child’s ranking in the income distribution compares to her parents'. If we use the old cliche of a ladder, it’s how far up, or down, the ladder you move compared to the quintile you were born into. If your parents were in the bottom quintile and you move into the second quintile, you have experienced relative mobility.

But what does that mean? Well, nothing really to you, unless you know what quintile you are born into and pay incredibly close attention to it. Relative mobility is a zero-sum game, if you move from the first quintile to the second, that means someone else has dropped downward. The numbers have to add up in the end. “Absolute mobility” measures something entirely different. It measures how your income compares with your parent’s income. So let’s say your parents make $10,000 a year and you are in the bottom quintile. If you stay in the bottom quintile, but make $20,000 a year, you’ve experienced absolute mobility.

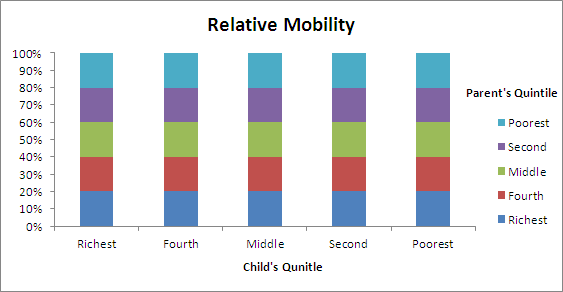

Relative mobility is important, but the big question is absolute mobility. Imagine a society where relative mobility looks like this:

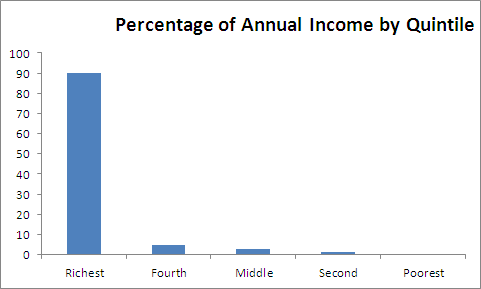

That is, no matter where you are born, you have a 20% chance of landing in any income bracket. But with an income distribution looks like this:

That society is perfectly mobile, but certainly one we don’t want to live in. To give everyone a decent shot at life means not just making sure they can move into another quintile, but that no matter what quintile they end up in, they can live a fulfilling life. Upward relative mobility for me means downward relative mobility for thee. Far better would be a society where all boats are rising together, rather than just a couple of yachts.

The problem is that in the last few decades, relative mobility has stayed pretty much the same (although, lower than most developed countries), but absolute mobility hasn’t been doing quite as well, mainly because of rising inequality. Josh Bivens calculates that if incomes had risen proportionately, the median income would be $19,000 higher.

The story of the past forty years has been an increasing share of the national income going to the top one percent, and little “trickling down” to the bottom. Because of this increase in inequality, it matters far more where you are born into on the income ladder. That’s a problem.