Most available research indicates a significant difference in priorities between the majority of Americans and the affluent that comprise the political donor class, which may explain the current bi-partisan drive for deficit reduction at the expense of stimulus policies, in spite of persistent high unemployment.

1. Does Washington really care about job creation?

Despite near-record levels of unemployment and meager economic growth, the U.S. political system has focused far more on deficit reduction over the past two years than on job creation. Austerity dominates the current political debate even as the economy struggles to recover from the Great Recession. Bowing to political pressures, President Obama created a national fiscal commission in early 2010 to recommend ways to tame the national debt, and discussion about deficit reduction has dominated Washington since then.

As a result of the debt ceiling showdown last summer, Congress enacted significant spending reductions in the Budget Control Act of 2011, despite predicted near-term job losses.

The Budget Control Act set a cap on spending on discretionary programs from FY 2013- 2022 at $1.5 trillion less than current levels. The Act also required across-the-board cuts (sequestration) if the “supercommittee” on deficit reduction failed to come up with adequate measures. As no compromise was reached, without Congressional action, the sequester will begin to take effect in FY 2013. Regardless, $1.5 trillion in spending cuts over a decade will be required starting next year, even if the sequester is avoided, bringing discretionary spending to the lowest level relative to the economy since the Eisenhower administration. If automatic spending cuts occur, an additional estimated 2.1 million jobs will be lost.

During this same period, proposals to address high unemployment and create jobs have seen far less traction in the national policy debate. There was no jobs commission created despite the high unemployment rate. President Obama’s American Jobs Act, introduced in September 2011, went nowhere in Congress and received only modest media attention. Even a bill specifically targeted at helping war veterans, a popular constituency, failed to garner enough support to overcome a filibuster last summer.

In many ways, Congress has exacerbated the jobs crisis. Even as states struggled to recover from the recession, Congress failed to provide much-needed relief to the states to save critical jobs and services, citing concerns about federal spending and the national debt. The failure to provide adequate aid to state and local governments resulted in over 600,000 public servants being laid off since the beginning of 2011. If the public sector had grown, as it did during previous recessions, there would be 1.2 million more public sector jobs, 500,000 more private sector jobs and a lower overall unemployment rate.

While a number of factors may explain this hierarchy of priorities in Washington, one point is clear: The focus on deficit reduction over jobs has reflected the concerns of affluent Americans and financial interests while downplaying an urgent desire by a majority of Americans to address job creation.

2. Would further deficit reduction help the economy?

Austerity advocates have successfully promoted the argument that without deficit reduction, our economy will suffer from inflation and high interest rates.

In turn, they argue, inflation and high interest rates will dissuade investment and cause the economy to contract. Austerity advocates also argue that keeping interest rates low reduces the value of the dollar. Our exports then become cheaper, imports become more expensive and the increase in exports creates jobs.

However, there is no evidence to support the fear that our deficit levels are threatening this kind of inflationary response. As long as output is depressed, the economy experiences little if any inflationary pressure. Interest rates are at historic lows and the Fed has indicated that it will keep rates low at least through mid-2013.

Treasury bond rates are currently at 2.56 percent

as investors across the globe seek out US government debt as a safe investment, belying the fear of bond market reprisals for federal deficits. Currently low interest rates have also done little to create export jobs. In fact, increased government spending is a more successful path to deficit reduction than deep spending cuts

as targeted spending would put more Americans back to work, addressing the second largest reason for our current budget deficits: the economic downturn.

Public investments, such as large-scale infrastructure projects, create jobs and increase economic activity. The increased economic activity would generate more revenue; a far more effective way to reduce the deficit than spending cuts that will cause the economy to contract. European countries offer a real-time example of how austerity can push recovering economies deeper into recession. Steep cuts to the public sector in several European countries have caused their economies to shrink, pushing them back into recession. The cuts also resulted in increased unemployment rates and perceived panic about debt caused interest rates on sovereign bonds to soar, making it difficult, if not impossible, to borrow money.

3. Do voters really favor deficit reduction over job creation?

By and large, the public prioritizes job creation over deficit reduction. Polling conducted after President Obama’s reelection found that 49 percent thought the election was a mandate for job creation while only 22 percent said that the President’s mandate was for deficit reduction.

Exit polls after the 2012 election also show that job creation was a priority over deficit reduction. When given the choice between spending money to invest in infrastructure/public sector hiring, like teachers and firemen, versus cutting spending to reduce the deficit, 52 percent said that we should be spending money while only 43 percent said that we should cut spending for deficit reduction.

The same poll found that 49 percent said job creation was the most important issue while 41 percent named deficit reduction as the most important issue. This gap is even larger for the rising electorate1 where 46 percent named job creation as the most important issue and only 33 percent identified the federal deficit. NBC’s exit poll showed that only 15 percent of voters thought the deficit was the biggest problem facing the country.

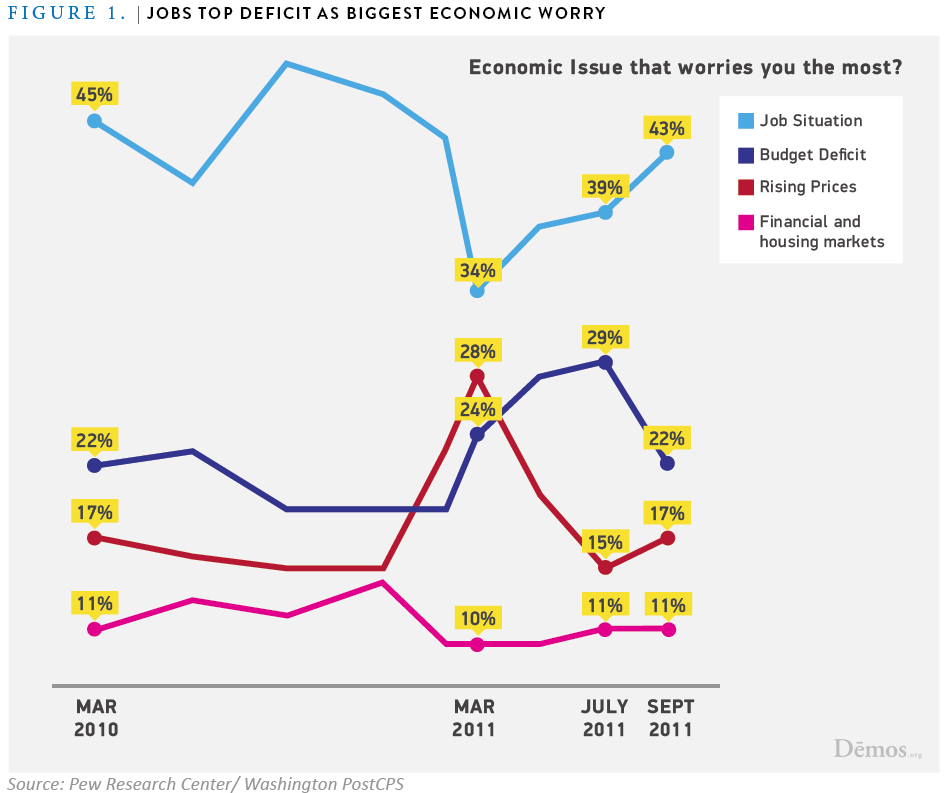

Public preference for job creation is not a recent trend. Polls over the past two years have repeatedly found that while many Americans are worried about deficits and the national debt, addressing unemployment and improving the economy has consistently been a bigger priority for the public. For example, a June 2010 NBC News/Wall Street Journal Poll found that 33 percent of Americans named job creation and economic growth as their top priority; 15 percent named “deficit and government spending.” A FOX News/Opinion Dynamics Poll that same month found a similar spread, with 32 percent naming jobs as a top priority compared to only 12 percent that named the deficit.

Most polls throughout 2011 and 2012 found that the public remained focused on jobs and the economy over the deficit by two-to-one margins or more.

The chart below shows how Pew Research Center polls find that job creation remains a top priority over time.

4. Okay, but what do the donors want?

The “donor class”—the segment of the population that donates to political campaigns—is disproportionately comprised of affluent Americans. Of those that contribute more than $200 to a campaign (the point at which detailed disclosure is mandatory), 85 percent have annual household incomes of $100,000 or more.

An annual income of $100,000 puts a household in the richest 20 percent of income earners.

In contrast to the majority of Americans, the donor class does not prioritize policies to create jobs and economic growth. While little data is available on how affluent Americans view national priorities, a few surveys do explore this issue. For example, a September 2012 survey by the Economist magazine found that respondents making over $100,000 annually were twice as likely to name the budget deficit as the most important issue in deciding how they would vote than middle- or lower-income respondents.

A 2011 Russell Sage Foundation study explored how wealthy respondents prioritized different policy choices. The survey found that 87 percent of affluent households believed budget deficits were a “very important” problem, the highest percentage of all listed perceived problems.

The authors of the study comment further:

One third (32%) of all the open-ended responses mentioned budget deficits or excessive government spending, far more than mentioned any other issue. At various points in our interviews, respondents spontaneously commented on “government over-spending.” Unmistakably, deficits are a major concern for most of our respondents. Nearly as many of our respondents (84% and 79%, respectively) called unemployment and education “very important” problems. However, each of these problems was mentioned as the most important by only 11%, making them a distant second to budget deficits among the concerns of wealthy Americans.

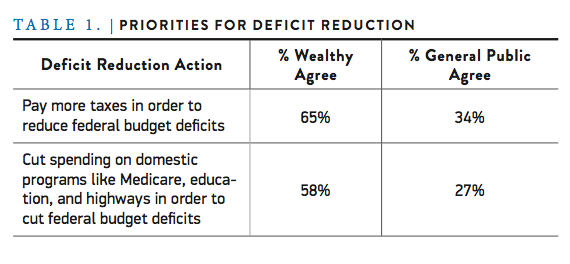

Reducing the budget deficit is seen as so important to the affluent that a strong majority of them are willing to pay more taxes in order to reduce the federal deficit (65 percent) or cut domestic programs like Medicare, education, and highways (58 percent) for deficit reduction. In contrast, only 34 percent of the general public are willing to pay more taxes and only 27 percent favor spending cuts for deficit reduction.

5. What do large corporations and executives want?

Wall Street interests also heavily advocate for debt reduction. The “Fix the Debt” campaign has raised $60 million and recruited 80 corporate CEOs to lobby for a deficit reduction plan that would lower corporate taxes and place the cost burden of deficit reduction on lower income and elderly populations.

Combined, the 95 companies that make up Fix the Debt have spent almost $1 billion on lobbying and campaign contributions over the past four years.

In fact, 22 of the companies have spent more on lobbying than they have paid in taxes in the past three years.

If the Fix the Debt plan is adopted, 63 of the companies represented would gain as much as $134 billion in tax windfalls by being allowed to repatriate funds without paying taxes. To pay for this windfall, deep spending cuts would be made to safety net programs such as Medicare. On an individual level, the CEOs backing the plan received a combined total of $41 million in savings last year due to Bush-era tax cuts.

6. Do the wealthy even care about job creation policies?

One reason that the affluent may be less concerned about job creation is that they have generally been less affected by high unemployment rates and the economic downturn than other groups. Unemployment rates vary greatly based on educational attainment, which also corresponds to affluence. The unemployment rate for those with less than a high school diploma was 12.2 percent in November 2012.

The unemployment rate in November 2012 for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, however, is 3.8 percent – a rate which is considered virtually full employment by most economists. More generally, upper income Americans were less negatively affected by the Great Recession and have recovered more quickly.

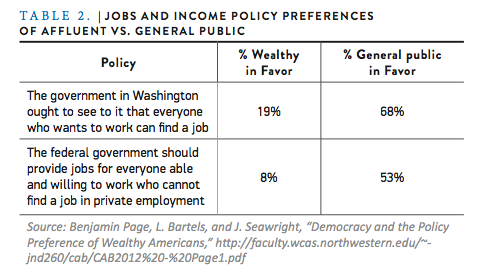

In addition to these factors, the affluent are significantly less inclined than other groups of Americans to support an active role for government in addressing mass unemployment. As the authors of the 2011 survey of wealthy Americans report:

Most striking, given the high importance that the wealthy attribute to the problem of unemployment, is their overwhelming rejection of federal government action to help with jobs. Only 19% of the wealthy say that the government in Washington ought to “see to it” that everyone who wants to work can find a job [presumably a private job]; 81% oppose this. A bare 8% say the federal government should provide jobs [presumably public jobs] for everyone able and willing to work who cannot find a job in private employment. Fully 91% disagree.

In contrast to this perspective of the affluent, majorities of the public generally support active government efforts to create jobs, including direct job creation. Several polls show majorities of Americans want the government to support efforts to increase employment. A 2011 NBC News/ Wall Street Journal poll found that 62 percent of Americans think the government should pay to retrain long-term unemployed workers.

During the height of the recession in 2009, a Bloomberg poll found that 70 percent of Americans thought government should pay for worker training for the unemployed.

The same poll found that a significant majority thought the government could directly create jobs: 66 percent favored job creation through spending money on public works, such as roads and bridges and 60 percent favored increased government spending on alternative energy. These findings were confirmed in a 2011 poll commissioned by the Ms. Foundation that found 62 percent of Americans think the government should focus on job creation, even if it increased the deficit in the short-term.

Conclusion

The influence of money in our political system goes beyond the money spent on elections. Money also influences the policymaking process, as evidenced by how well the interests and priorities of the affluent class are represented in Congressional action—even when they run counter to the wishes of most Americans. Removing the outsized influence of the affluent in policymaking is necessary not only for the democratic process but to ensure that our economic recovery continues.