Democracy has at its heart a basic promise: citizens have an equal voice in deciding who represents them.

This promise went unfulfilled again in 2014. Large donors accounted for the vast majority of all individual federal election contributions this cycle, just as they have in previous elections.

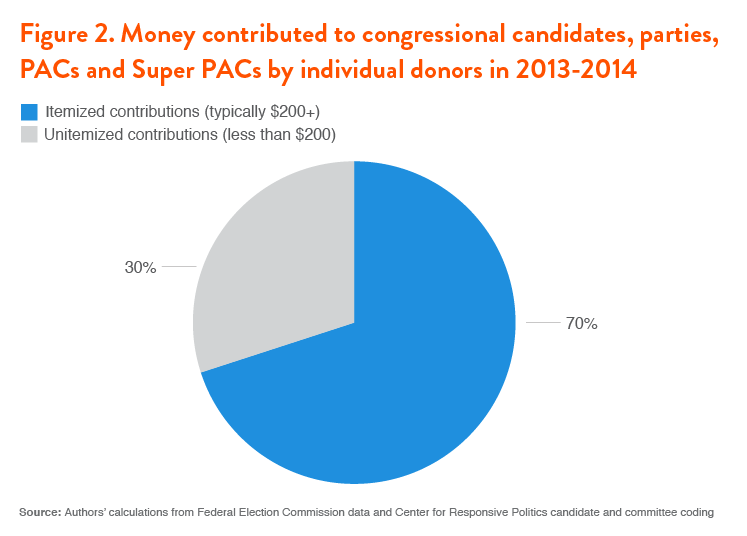

Seven of every 10 individual contribution dollars to the federal candidates, parties, PACs and Super PACs that were active in the 2013-2014 election cycle came in itemized contributions, which typically come from donors who give $200 or more.

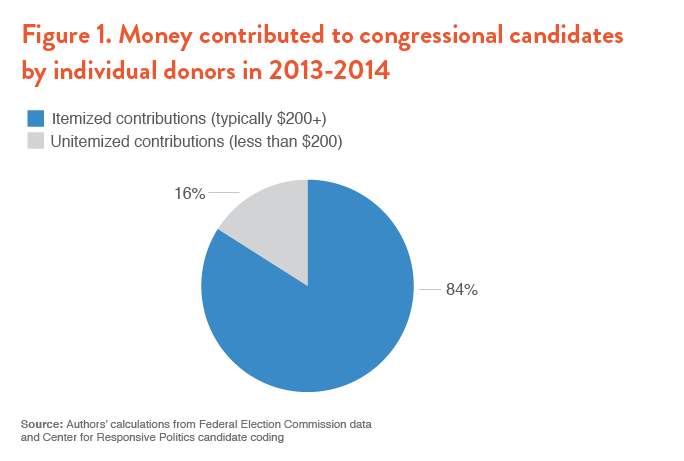

Candidates alone got 84 percent of the funds they raised from individual donors in itemized contributions.

And these overall numbers can obscure the especially outsized role large donors play in some cases. Just 50 individuals and their spouses accounted for more than a third of the total money raised by Super PACs this cycle.

Many candidates, including some whose individual contribution totals reach into the millions, report receiving few dollars in contributions from small donors.

Voters feel this mismatch between the promise of equal democracy and the reality of unequal voice. Fully three-quarters of respondents to a CBS News poll conducted earlier this year said the wealthy have more influence over elections than other Americans.

Unsurprisingly, voters worry that this inequality in electoral influence translates into an inequality in representation when election winners take office. Echoing the results of earlier surveys, an Every Voice poll conducted after the 2014 elections found that just 11 percent of Democratic voters and 15 percent of Republican voters think constituents are even among the top two biggest influences on their representatives’ votes, versus groups like lobbyists, campaign donors and special interests.

And they’re often right. According to new work by Brigham Young University’s Michael Barber, the gulf in policy views between some senators and the average constituent in their states is so wide it’s almost as if they were assigned randomly to represent voters rather than being elected by them.

A high-profile study by Princeton University’s Martin Gilens and Northwestern University’s Benjamin I. Page reveals that economic elites and business interests play an overwhelmingly more significant role in setting policy than average citizens. “Not only do ordinary citizens not have uniquely substantial power over policy decisions,” Gilens and Page find, “they have little or no independent influence on policy at all.”

The obvious response to this stark disparity between the system we have and the democracy we deserve is to take steps to bring the former into closer alignment with the latter. The first step we can take is to match small donors’ contributions with public funds, to amplify their voices and provide an incentive for candidates to listen to all voters rather than just elite donors.

Unfortunately, the other natural response—directly limiting big money—has been largely closed off by a Supreme Court that has narrowed the legally allowable justifications for limiting big contributions or spending to just fighting quid pro quo corruption, or bribery.

That’s far too low a bar. Democracy means more than just the absence of explicit money-for-votes schemes. It’s long past time to demand that a true conception of democracy play a more robust role in our campaign finance policies. That means pushing the Supreme Court to recognize that our democracy contains the promise of political equality for all citizens regardless of wealth, clearing the path for our elected representatives to enact policies that end large donor dominance of our elections.

In January, we will release a report that documents the full extent of the role large donors play in our elections and explains the long-term changes needed to bring our policies more in line with our promises, as well as how we can work within current constraints in the meantime.

This Demos and U.S. PIRG Education Fund analysis is part of #Money14, a series of independent reports exposing the role of money in American politics. Join us for an event near the fifth anniversary of Citizens United to hear more about the participating organizations’ innovative research and work together for a more inclusive, transparent, and participatory democracy.