As of this writing, DMV’s discussions with advocates indicate that it has implemented a largely automated procedure for voter registration during in-office and online driver’s license and identification card applications and renewals. To date, however, the DMV continues not to offer NVRA-compliant voter registration services during renewal transactions conducted by mail, which account for more than 1 million renewal transactions per year. As a result, in May 2017, Demos and its partners initiated a lawsuit against DMV and the Secretary of State to compel the State to come into full compliance with the NVRA.

As discussed further below,

the improvements in DMV’s in-person and online processes have already resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of voter registrations submitted through the DMV. Between implementation of those improvements in May 2016 and the November 2016 election, registrations during in-person and online DMV transactions increased by about 50 percent as compared to the number received during the same period leading up to the 2012 presidential election.

Demos’ research indicated that as of 2014, the DMV in Nevada, like California, was registering only a tiny fraction of the voters who engaged in driver’s license transactions, and requiring customers to jump through a series of hoops to get registered. As described in Driving the Vote, the Nevada driver’s license application was highly confusing, and the procedure for registering to vote during a driver’s license transaction blatantly violated the NVRA.

A field investigation conducted in 2014 confirmed that these violations had a detrimental impact on the number of voters who registered through the DMV. Many customers Demos interviewed did not see the voter registration question and therefore did not affirmatively request an application. Worse, some customers who did check the voter registration box on the application form were not provided with a voter registration application unless they also asked for it.

At the time of the investigation, legislation was pending in the Nevada legislature that would have provided funding for the DMV to upgrade its information technology infrastructure, including technology that could be used to support voter registration. Demos contacted several Nevada-based advocacy groups that had supported the legislation to provide them with the information from our research and to offer technical assistance to ensure that any voter registration upgrades that came out of the legislation would be NVRA-compliant. After the DMV infrastructure bill failed, Demos continued to work with local advocates in an effort to bring about voluntary changes at the DMV.

In March 2016, when the local advocates concluded that their advocacy efforts had failed to yield results, Demos, Project Vote, and a local law firm sent a pre-litigation notice letter to the Nevada Secretary of State and Director of the Department of Motor Vehicles. In response to the notice letter, sent on behalf of the Mi Familia Vota Education Fund and an individual Nevada resident, Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval’s office, which oversees the DMV, expressed its strong commitment to achieving compliance, and helped facilitate settlement of the matter without litigation. In March 2017, after several productive meetings and months of good-faith negotiations, the parties entered into a Memorandum of Understanding that will bring the state into compliance with Section 5.

The MOU is structured to proceed in 3 phases. In Phase I, which was completed even prior to finalizing the MOU, the DMV worked with Demos and our partners to develop new paper driver’s license forms intended to remedy many of the Section 5 violations. The new forms were rolled out statewide in September 2016. In order to avoid requiring duplicate information, the state created a new voter registration application that allows the DMV to use its printers to pre-populate much of the application using the information provided on the driver’s license form. The application was designed in such a way that county registrars can use existing equipment and so ware to scan them into the statewide voter registration database. The new voter registration application is included as the final page in all driver’s license applications, and is mailed along with all driver’s license renewal notices. Customers who complete their driver’s license renewals online are provided with an opportunity to use the state’s Online Voter Registration system or to request a paper voter registration form from the DMV.

In Phase II, which was initiated at the end of January 2017 and completed in May, the state built an electronic link between the DMV’s computer system and the Secretary’s online voter registration system, so voter registration information, including a digitized signature, can be seamlessly transmitted between the 2 agencies. Furthermore, as a result of Demos’ engagement with state officials, Nevada is for the first time providing all DMV voter registration forms in Spanish throughout the state and in Spanish and Tagalog in Clark County.

Finally, in a third phase of improvements, estimated to be completed in 2020, the state has committed to further modernize its Motor Voter procedures as the DMV carries out a complete overhaul of its technological infrastructure.

“We are proud to deliver these enhancements to the citizens of Nevada,” said DMV Director Terri Albertson. “The DMV is a critical component in the voter registration process. We are dedicated to providing the service with security and integrity, as well as convenience.”

North Carolina

Unlike California and Nevada, North Carolina’s implementation of Motor Voter appeared to be compliant with the NVRA’s requirements for individuals who apply for or renew a license or ID card in person, and Driving the Vote placed the state solidly in the middle of the pack in terms of the number of voter registration applications originating at the DMV. However, evidence introduced in a lawsuit challenging the state’s elimination of same-day registration revealed that many voters who had attempted to register to vote at the DMV were denied their right to vote when they appeared at the polls only to find that their name was not included on the voter roll, suggesting that voter registration applications submitted to DMV offices were not being transmitted to election officials. Information provided by county Boards of Elections in response to public records requests showed that this problem was systemic. In addition, the state’s recently implemented online DMV services portal did not allow individuals renewing or changing the address on their license online to register to vote or update their voter registration information.

In June 2015, Demos and several partner organizations sent a letter on behalf of 3 local civic engagement groups and 3 individual North Carolina voters who had attempted to register at the DMV, notifying the state of these problems and seeking to engage the state in cooperatively developing a solution.

After an initial conversation with representatives of the State Board of Elections, the discussions broke down, and in December 2015, the organizations and individuals led a lawsuit seeking to compel compliance with the NVRA.

The lawsuit, which is still pending, has already pushed North Carolina to take preliminary steps to improve compliance with the NVRA. Specifically, the DMV integrated some voter registration services into its online renewal and change of address portals in 2016, though improvements still need to be made. Additionally, after the notice letter was sent, the DMV began requiring that an individual who declines voter registration services when they apply for, renew, or change the address on a license at a DMV office sign a form acknowledging that they declined voter registration services (a “declination form”). Despite the fact that the DMV is now using declination forms, problems persist, and individuals who request voter registration services at DMV offices still frequently find that their registration information has not been transferred to the Board of Elections. For this reason, efforts to bring the DMV’s in-office and online systems into compliance with the NVRA are ongoing.

Enforcement Actions by U.S. Department of Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) is charged with enforcement of the NVRA, and as the nation’s top law enforcement agency, it has the responsibility to move intransigent states to comply with federal law. After Demos shared Driving the Vote with DOJ officials, the department began to take an interest in enforcement of Section 5 of the NVRA for the first time since the mid-1990s. In 2015 and 2016, DOJ sent pre-enforcement letters to, and signed comprehensive memoranda of understanding with Alabama and Connecticut, 2 of the 3 states Demos identified as reporting the lowest rate of DMV voter registrations in the nation.

Alabama

The analysis in Demos’ 2015 report showed that Alabama was at the very bottom of the list in terms of collecting voter registration applications through DMV offices.

Our report ultimately exposed that in the 20 years since the passage of the NVRA, Alabama had never implemented Motor Voter. In September 2015, the DOJ sent a letter to Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill, notifying him that the state was not in compliance with the NVRA and threatening litigation should the state not revise its procedures.

Shortly thereafter, in November 2015, the Department of Justice entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with the State of Alabama, the Secretary of State, and the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA), the state agency that administers driver licensing.

Prior to the MOU, Alabama was out of compliance with Section 5 across the board. As Secretary Merrill acknowledged, “[W]e’ve never been compliant.”

The MOU between the state and the DOJ provides for an interim resolution using a paper voter registration form and, within 7 months of the date of the MOU, a permanent electronic system allowing seamless transfer of data between ALEA and the Secretary. In addition to developing a new NVRA-compliant system, Alabama also agreed to take steps to remedy years of past violations. Under the remedial plan, the Secretary was required to contact by mail and send a voter registration application to all Alabamians who have a driver’s license or identification card and do not appear to be registered to vote in Alabama.

The MOU authorized Alabama to participate in the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC)

as a means of identifying those to whom to send the remedial mailing.

Connecticut

Connecticut had one of the lowest rates of DMV registrations in the country, according to Demos’ analysis in Driving the Vote, and Demos’ research indicated that Connecticut’s procedures violated Motor Voter.

Indeed, the state’s standard driver’s license application contained no mention of voter registration at all.

Following an investigation, the Department of Justice sent a pre-litigation letter to Secretary of State Denise Merrill on April 16, 2016.

As the state had recently enacted an automatic voter registration requirement and was in the process of created a modernized, automated system of voter registration at the DMV, by May 2016 it had already developed a compliance plan. The parties subsequently signed a Memorandum of Understanding requiring considerable modernization of the state’s voter registration processes.

The electronic voter registration system put in place as a result of the DOJ’s enforcement action consists of an automated opt-out process seamlessly incorporated into every driver’s license transaction. In other words, every driver’s license application, renewal, or change of address serves as a voter registration application (or update if the customer is already registered to vote), unless the customer affirmatively indicates she does not want to register. For all NVRA-covered transactions, the DMV computer system requires a response to the voter registration question from the employee before completing the transaction. All voter registration applications are electronically transmitted to local election officials through a daily upload to the statewide voter registration database. DMV forms used for remote address changes and renewals have also been updated to comply with the NVRA and work with the new electronic system.

Like the Department’s MOU with Alabama, the agreement with Connecticut requires a robust recapture procedure to reach out to citizens who have not been provided NVRA-compliant opportunities in the past. Connecticut, which is already a member of ERIC, is required to identify eligible citizens within the state who have a driver’s license or identification card but who are not registered to vote, and to provide them with a voter registration application by mail. This outreach must be conducted periodically through the 2018 general election.

Section II. Impact

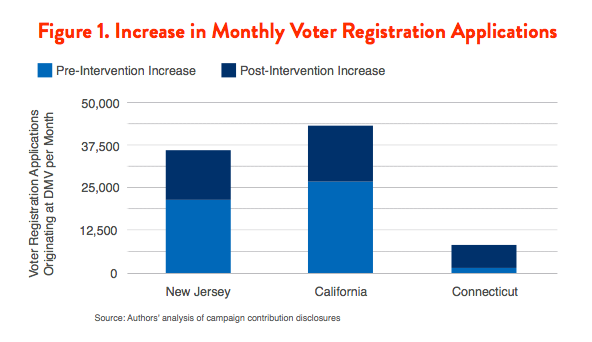

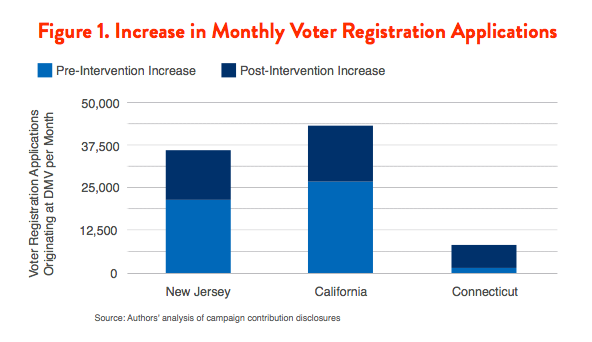

The improvements states have made in their Motor Voter programs since the publication of Driving the Vote have already begun to increase the numbers of voter registrations originating at their motor vehicle agencies. To get a sense of this impact, Demos calculated how many additional voter registrations were generated through driver’s license transactions after the states implemented their reforms, as compared to their prior performance.

We started by looking at data collected by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) indicating the number of voter registrations that came from the motor vehicle agency for each state. In conducting our analysis, we chose the EAC’s data from 2012, covering the latest presidential election cycle for which data is available, rather than the more recent 2014 data, to help ensure that changes in the number of registrations we observed were attributable to Motor Voter reforms and not to increases in registration typically seen in a presidential election year.

To standardize the data, we calculated a monthly average number of registrations received from the DMV by the states during the 2011-2012 election cycle.

We similarly calculated the monthly average number of registrations received from the DMV following implementation of the Motor Voter improvements described above. Finally, to understand the impact of the reforms, we looked at the difference between the monthly average of registrations pre-and post-reform.

The results are encouraging. In all states where data were available, the monthly average number of voter registration applications produced by the DMV increased dramatically. For example, the average number of registrations per month in Connecticut, the state that adopted the most comprehensive reforms, was 8,671 from the date of the state’s MOU with the Department of Justice through March 2017, as compared to only 856 per month in the 2 years before the 2012 election, an increase of roughly 7,800 voter registration applications per month, or over 900 percent. In California, where reforms have not yet been completely implemented, the number of voter registration applications originating from the DMV increased to 41,918 per month from April through October 2016, from an average of 27,404 per month in the same period in the 2012 presidential election cycle, a 53 percent increase. Figure 1 summarizes the impact of Motor Voter reforms in the 3 states for which data were available.